Blog

The Biophilic Mind: A Walk in the Park to Reduce Rumination

If you have been following along on this blog, you are well aware of the benefits of experiencing nature. I am excited to share today’s study because it shows the same potential benefit in two ways, because twice the evidence is always better!

A 2015 study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences aimed to link good mental health to experiences in nature using both self-reported data and brain imaging. Using two methodologies like this can be especially convincing because showing an effect two different ways (behaviorally and biologically) is stronger evidence that the effect may be real.

Now for the study.

All 38 participants in the study first had their brains scanned (more on that below) and completed a survey that asked about their mental health. Specifically, they answered questions about how much they engaged in a thought process called rumination, which is a pattern of repeatedly focusing on one’s shortcomings and negative emotions (see Table 3 here for the specific questions they asked). Rumination has been linked to depression, as repeatedly focusing on one’s perceived flaws can draw one into a depressive episode.

The authors then randomly assigned participants to take a 90 minute walk in nature or along a busy city street, after which they returned to the lab for another brain scan and took the survey about rumination again.

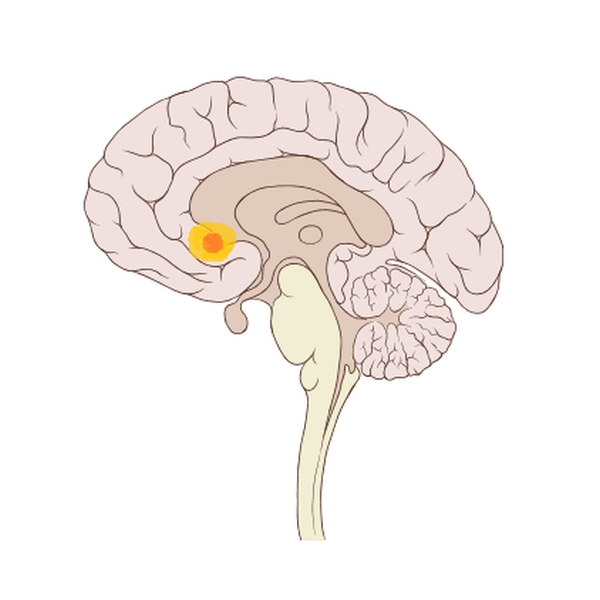

The authors predicted that walking in nature would reduce both self-reported rumination and evidence of rumination in the brain — but what would that evidence look like? Unfortunately, there is no “rumination” part of the brain that is only activated when you are ruminating. Instead, several careful studies over the years of brain imaging can tell us which brain regions are most strongly activated when people are ruminating. They do this by instructing people to ruminate in the brain scanner and looking for regions with increased blood flow compared to people at rest (and not ruminating). These studies show that a specific part of the brain called the subgenual prefrontal cortex (the sgPFC for short) is especially active during rumination, so that is where they looked.

The subgenual prefrontal cortex (sgPFC). Photo by Patrick J. Lynch, medical illustrator, altered by the author

What did they find?

First, there was a decrease in self-reported rumination in the nature walk group but not the city walk group. However, the nature walk group initially had higher levels of rumination than the city walk group (even the post-walk score of the nature group was higher than the city group), and the authors do not report if this initial difference between groups was statistically significant. Thus we cannot know for sure if there was a failure of randomization in the study—that is, participants in the two groups were different in an important way. Perhaps people with higher levels of rumination happened to be more likely to be assigned to the nature group.

Even with that limitation, the authors report a decrease in brain activity in the sgPFC for participants who took the nature walk, but not participants who took the city walk. Importantly, there were no group differences in how people responded physiologically (e.g., no differences in heart rate or respiration), which makes it more likely that walking in nature actually decreases activation in the part of the brain that is most associated with rumination.

What do you think about this study? Do you find the converging evidence of the self-reported decreases in rumination and the decreases in activity of the sgPFC convincing, or do the shortcomings of either method leave you wanting more evidence? We can also think about how strong the “dose” was in this study—90 minutes is a long time for a walk! Do you think the results would hold if the walks were shorter? How long do you think these benefits last?

Footnote: For further reading on this topic, see this Psychology Today article.

Photo credits: Pixabay users adage, Gerd Altmann, and Foundry.