Blog

#bioPGH: Zugunruhe!

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

If you’ve been watching real-time migration maps on BirdCast, you’ve noticed that fall migration is well underway for our birds in Eastern US! That means that around this time, birds are experiencing something call zugunruhe. Zugunruhe is a German word to describe the “migratory restlessness period” experienced by migratory animals, particularly birds. It’s an internal cue that wild birds use to begin their seasonal migrations (if they migrate). What exactly is this restlessness, and what causes it? Let’s explore!

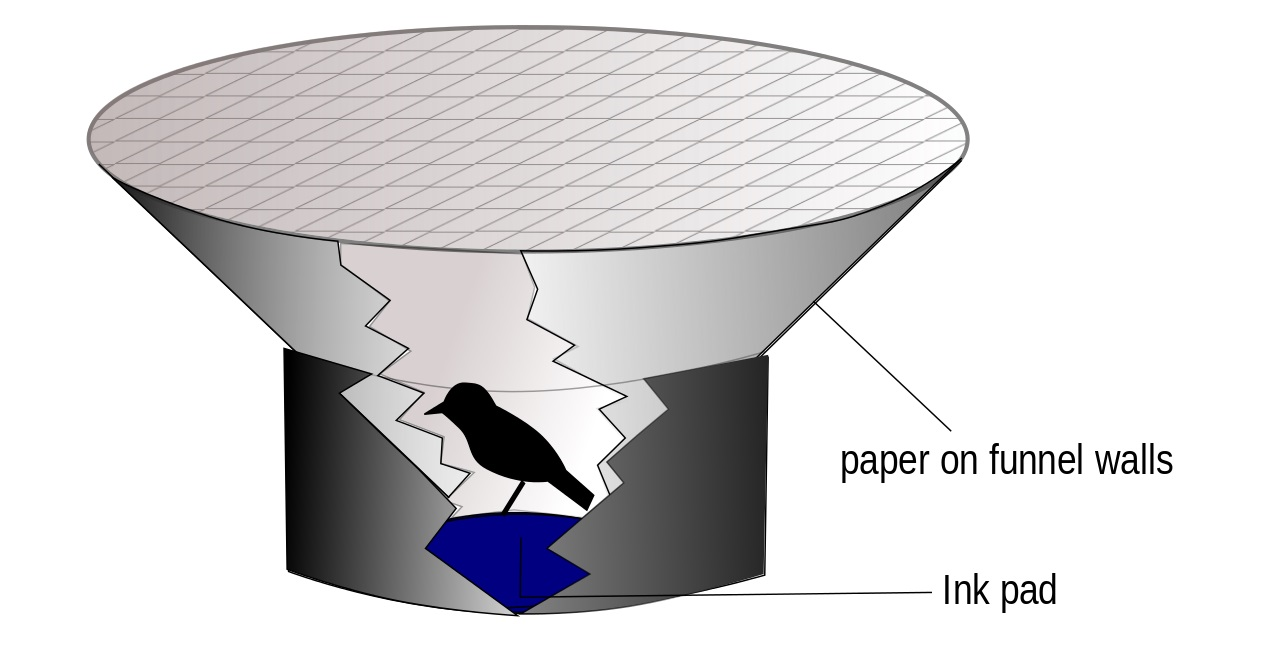

This season of restlessness has been studied primarily in migratory birds in human care, such as birds in wildlife centers, labs, or zoos. During the time that these birds would normally need to begin their migrations, such as the fall or spring, they become distinctively more active—hopping in place, increased wing flutters, and general increased activity. In 1966, a researcher duo developed a way to quantitatively measure this restlessness in a lab through what came to be known as an Emlen funnel (after authors Emlen and Emlen, see image below). A bird perches at the base of this “funnel” on an ink pad. The walls of the cone are covered in paper to catch the footprints of the bird and serve an indicator of activity, and the top of the cone has a wire mesh across the top to contain the bird.

Wikimedia Commons, public domain

The Emlen funnel has been used over the decades to learn quite a bit about zugunruhe. During non-migratory times of the year, for example, a bird sitting at the base of the funnel might explore the top or might hop around the funnel, but not with any particular urgency in a particular direction. During the start of migration times, however, birds not only increase activity—fluttering their wings and hopping about the funnel—but they are keyed in to a particular direction. If these birds are able to see the night sky, they correctly identify the direction they would be traveling for their species’ migration (southwest, for example) and leave a concentration of little footprints on the southwest side of the funnel. In the absence of a constellation cues, the birds orient using magnetic north as a baseline (both migratory and non-migratory birds seem to have an internal magnetic compass).

One may wonder, how do these birds know to be restless? Phenology, the study of the timing of events in nature, is complicated and always includes a variety of factors, but we have some important clues for birds. Photoperiod (day length) seems to be an important migration cue, as does resource availability and genetics. Hormonal changes also seem to be an important factor not just for initiating migration, but also for guiding how birds manage their time at stopovers while migrating (like taking a break at rest stop).

While pulling up my references for this post, I stumbled across a few different popular articles addressing “human zugunruhe.” I was intrigued since I hadn’t explored the idea before (and a colleague had even recently asked if it was a human phenomenon as well.) As I read into the articles, though, I think what they were describing was more like wanderlust—an interest traveling and exploring for the sake of exploring, rather than an intentional change in location based on seasonal resource availability. Though “wanderlust” is a very Instagrammable hashtag, the intense desire to log new experiences and go on adventures is a human phenomenon with science behind it just as zugunruhe is a bird characteristic with science behind it. Or perhaps we just haven’t explored all possible angles of zugunruhe in non-avian vertebrates. That’s the best part of science—we always have more to keep learning!

Connecting to the Outdoors Tip: If you’re interested in learning more about bird migration, or even seeing some birds in transit, check out the Allegheny Front Hawk Watch or the bird banding lab at Powdermill Nature Reserve.

Continue the Conversation: Share your nature discoveries with our community by posting to Twitter and Instagram with hashtag #bioPGH, and R.S.V.P. to attend our next Biophilia: Pittsburgh meeting.

Photo credits: Pexels, public domain