Blog

#bioPGH: The Boom Over the ‘Burgh

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

Late morning on New Year’s Day, with the marching bands of the Rose Bowl Parade in the background, I settled onto the couch with round two of coffee and lazily checked headlines on Twitter. Like many other Pittsburgh folks, I was startled to see the below Allegheny County tweet:

Allegheny County 9-1-1 has received reports of a loud boom, shaking in the South Hills and other reports. We have confirmed that there was no seismic activity and no thunder/lightning. At this point, we have no explanation for the reports, but agencies are continuing to look.

— Allegheny County (@Allegheny_Co) January 1, 2022

An unidentified…explosion? I hadn’t heard anything myself, though social media was bursting with anecdotes of shaking windows and loud booms. Within a short period of time, though, the answer proved to be less ominous and more exciting: there had been a meteor over Western Pennsylvania! The boom and shaking had been the meteor hitting our atmosphere and exploding up in the sky. I checked in with Matthew Kramar of Pittsburgh’s National Weather Service to learn a bit more about the event and how they determined it had been a meteor.

“It was a bit of detective work, really!” Kramar said. “And our forecasters had the science to put the clues together.”

Let’s follow along, but first we can review the evidence we all were able to observe ourselves: a loud boom, noticeable shaking in homes, but no thunderstorms or earthquakes.

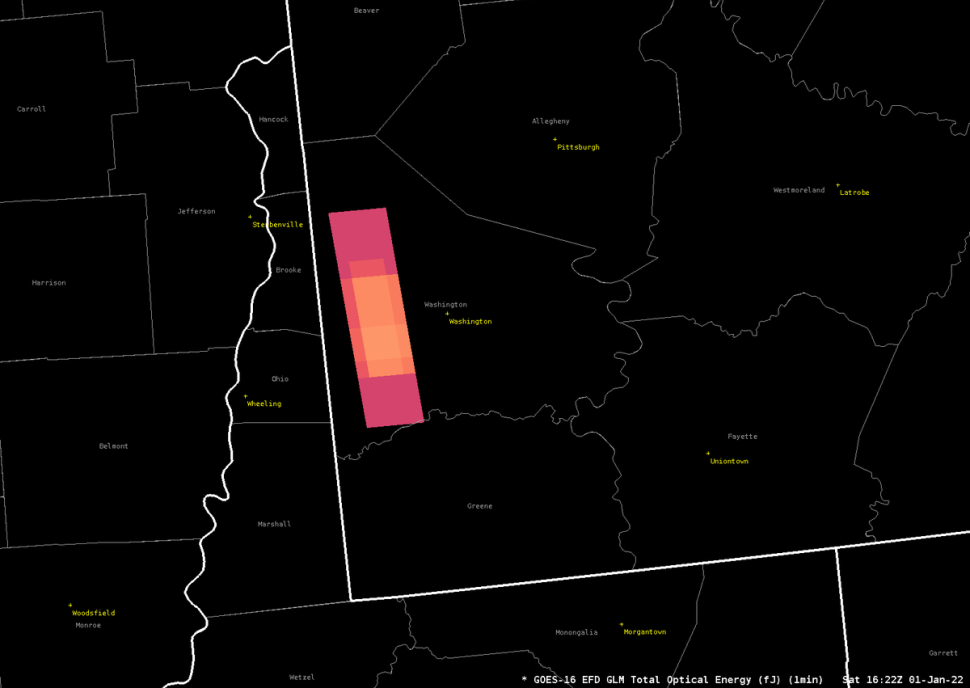

One of the biggest pieces of the puzzle was actually a bright flash of light that we couldn’t see because of heavy cloud cover that morning; that bright flash that was ultimately detected by the GOES 16 satellite. GOES 16, launched in 2016, has a feature called the Geostationary Lightning Mapper. This detects flashes of light that normally correspond with flashes from lightning in a thunderstorm, and it can identify a region of the atmosphere where the appearance of light came from. On Saturday morning, though, our meteor tricked the light sensor into thinking there was a lightning strike — visible on the map below as blocks of color.

Credit: National Weather Service

The elongated blocks were actually a major clue that the Saturday’s surprise had not been lightning. Normally, lightning appears on the data map as small circles pinpointing the location of the lightning strike. Since this was a meteor streaking across the sky, rather than small, localized circles, we see a blocky streak on the map.

Kramar also noted that while GOES 16 detected light flashes, other weather equipment meant to detect lightning didn’t react all. For example, ground-based sensors that detect electrical charges from lightning didn’t record anything during the time of the boom.

“And of course we knew there were no thunderstorms in the area,” said Kramar, “so we knew it had to be something different and something in the atmosphere — and there’s only so many things it could be.”

All of this made a meteor look like the most reasonable possibility, especially considering we’re in the middle of the Quadrantid meteor shower. Less famous than the Geminids and Leonids meteor showers, the Quadrantids still apparently can pack quite a punch! (And they will be visible from December 26th to January 16th, 2022.) According to NASA’s Meteor Watch, an infrared sound station tracked the soundwaves from the meteor’s explosion, estimated that the meteor would have been roughly 18 inches in diameter, weighed half a ton, and would probably have been traveling at 45,000 miles per hour. When the meteor burst upon hitting the atmosphere, it would have exploded with the force of 30 tons of TNT! No wonder our region heard some loud booms!

As exciting as this sounds, though, one might wonder, do we need to be worried about any other, larger meteors making it to Earth?

“Meteor showers happen pretty often — probably more often than we realize because of cloudy skies or light pollution,” noted Kramar. “But the important thing here is we saw that the atmosphere is doing its job of breaking them up before they cause damage.”

Connecting to the Outdoors Tip: If you’d like to catch any more of the Quadrantids meteor shower (though perhaps not literally!), check out this viewing guide from USA Today. The shower will be visible until later this month.

Continue the Conversation: Share your nature discoveries with our community by posting to Twitter and Instagram with hashtag #bioPGH, and R.S.V.P. to attend our next Biophilia: Pittsburgh meeting.

Thank you to Matthew Kramar of Pittsburgh's National Weather Service for his time and assistance with this post.

Photo credits: Cover, NASA, Perseid meteor shower; Header, Pixabay, Milky Way