Blog

#bioPGH Blog: What’s in Bloom?

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

On these late summer evenings, when the sun is casting long shadows earlier and earlier, one magical transition to watch is a meadow shifting from mid-summer to early fall flowers. Walking my puppers every evening means I have the unique opportunity to watch this transition in real time at one of our local county park meadows; there is still some lingering bee balm, purple cone flowers, and butterfly weed here and there, but classic fall flowers are blooming en masse as well. Let’s check out what’s in bloom!

Goldenrod

Image by Wikimedia User: liz west, CC-BY 2.0

A late summer staple, goldenrod is the common name for the Solidago genus of the Aster family. The genus boasts more than 100 species, most of which are native to North America and produce tall spikes of showy flowers in varying yellow hues and can bloom from August to October. Goldenrod is often unfairly blamed for the seasonal woes of fall allergy sufferers (like myself), but it actually has heavy and sticky pollen that does not travel well in the air – it must be pollinated by a variety of insects like bees, wasps, flies, beetles, and butterflies. Instead, many of us are actually feeling the effects of ragweed, whose pollen can be airborne.

New England Aster

New England asters (Symphyotrichum novae-angliae) are members of the Asteraceae family native to eastern North America, from as far south as Georgia to the northernmost reaches of Quebec. They flourish in disturbed lands like along roadsides and in old fields, but they can also be a lovely addition to a native pollinator garden. They need full sun and prefer damp, loamy or even sandy soil; and they can grow to be five-six feet tall – and this one I took a picture of at Boyce Park was indeed just shy of my height of six feet! Their range of color varies from a light blue to a violet purple.

Smooth Blue Aster

Much shorter than New England asters, smooth blue asters (Symphyotrichum laeve) are noted both their smaller stature at 2-4 feet, and the smoothness of the tops of their leaves (as opposed to rough or hairy). These are relatively frost hardy and may keep blooming into later fall!

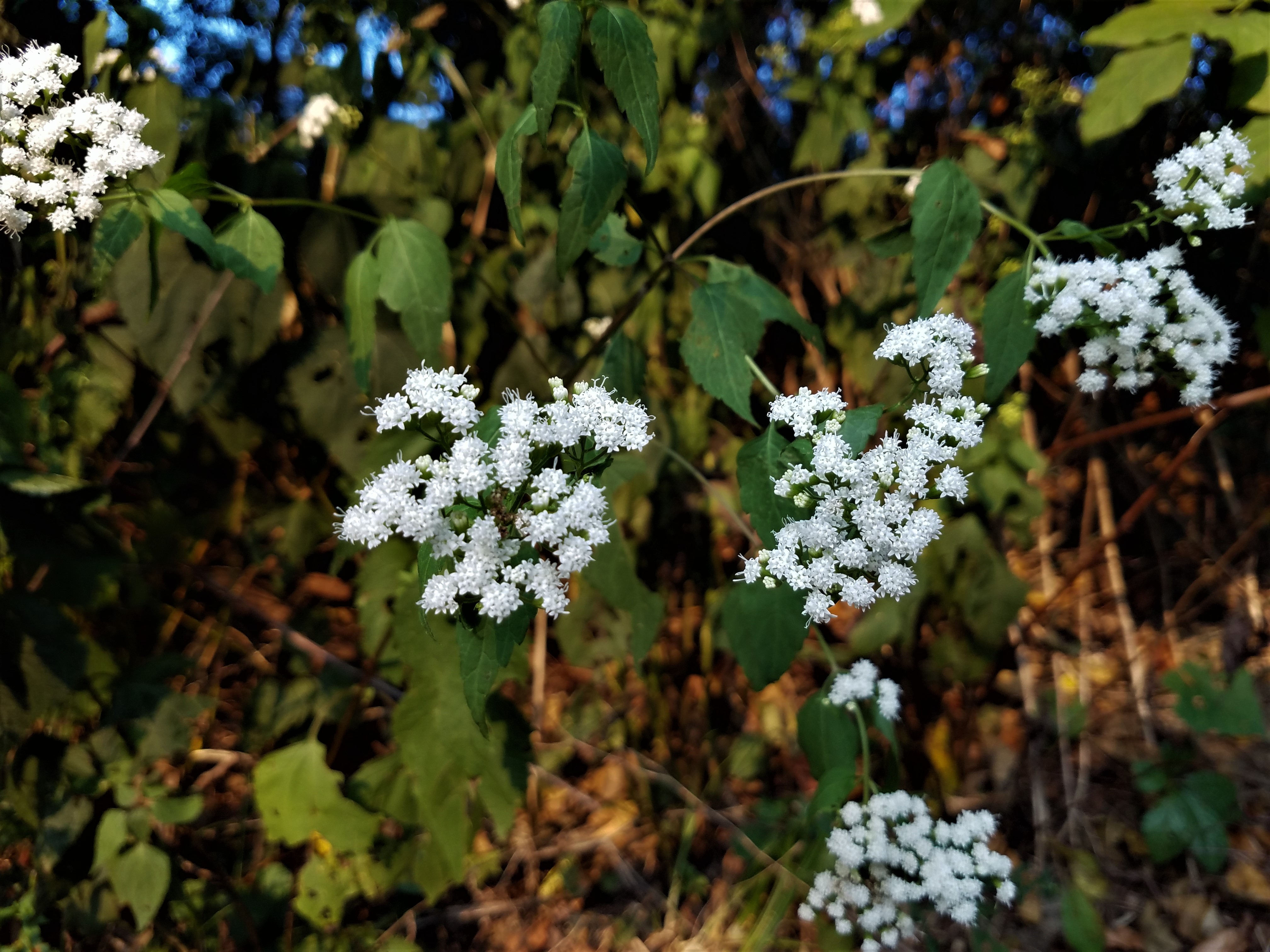

Late Boneset

Late boneset (Eupatorium serotinum), also known as late thoroughwort, is another fall-blooming aster that you have probably already seen this year along roadsides or perhaps meadows or pastures. Their tiny individual flowers are all disk florets; they don’t have ray florets like what appears to be the “petal” of a coneflower. They are often confused with a plant that blooms in a similar time frame, white snake root.

White Snakeroot

White snakeroot (Ageratina altissima) is also a member of the Asteraceae family. Like late boneset, white snakeroots don’t have ray florets, just disk florets. As the season progresses, the little white flowers will appear more “fluffy” late in the bloom, but each teeny bit of fluff is actually an achene, the same kind of dry, fluffy seeds as a dandelion. The flowers may look similar to late bonesets, but two plants can be easily distinguished by their leaves and, to some extent, height. Snakeroot’s leaves are shaped like long, rounded triangles while bonesets have distinctly elongated leaves. There is some overlap in height, but late boneset can grow 3-6 feet tall while white snakeroot tends to be 2-4 feet tall.

Now, I can’t quite let this plant go without telling its story. White snakeroot is also the infamous as the culprit behind “milk sickness,” a significant issue in the Midwest during European settler expansion of the nineteenth century. Shortly after drinking milk in late summer, victims would begin trembling and experience intense gastrointestinal distress and often death — and it was noted that the livestock of a person suffering from this milk sickness often had “the tremors” as well. The first documented description of milk sickness appeared in 1809, but in the 1830s, with the guidance of the Shawnee, Illinois doctor Anna Hobbs Bixby learned that cows and livestock ingesting white snakeroot could pass on the toxins from the plant in their milk. However, as she was a woman living in a remote area in the nineteenth century, it was difficult for her to spread this knowledge too far beyond her own community or be taken seriously on a broader platform. In academic literature, credit is often given to a set of brothers who published the same conclusion nearly a century after her.

Whatever the blooms you see, don't miss out on the late summer flowers! This Saturday is supposed to be a lovely day, be sure to get out and explore!

Resources

Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center: Smooth Blue Aster

Missouri Botanical Garden: White Snakeroot

MO Dept of Conservation: Late Boneset

Images: Cover, Maria Wheeler-Dubas; header, Ryan Hodnett CC-BY-SA-4.0; all other images by Maria Wheeler-Dubas unless otherwise noted.