Blog

#bioPGH Blog: Were They or Weren’t They? The Pennsylvania Bison Natural History Mystery

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

This week, as something a bit different from our usual outdoors explorations in this blog, I would like to invite you to walk through a nature mystery with me. Over this past weekend, the beautiful weather called many of us outdoors to local parks and nature preserves to explore; after adventuring in Raccoon Creek State Park, I came across a reference that suggested the area had possibly been a historic home to bison. Bison? I was surprised and quite intrigued—the solemn majesty of the Great Plains had once found a home as far east as our densely wooded hills? This was an idea I had to explore!

To answer this question, I tried to pull up as much historic information as I could. Were there records of bison in Pennsylvania? First, I found a paper from 1895 published by the Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia discussing how far east into the state bison were thought to have roamed—this must be it! As I read the paper, though, I realized that even this author from a century ago was discussing the hearsay of events that had happened a full century before him. I then did a bit more research on the remains of “bison” noted in the paper, and in the 1960’s, it was determined those teeth were more likely from a long-extinct musk ox.

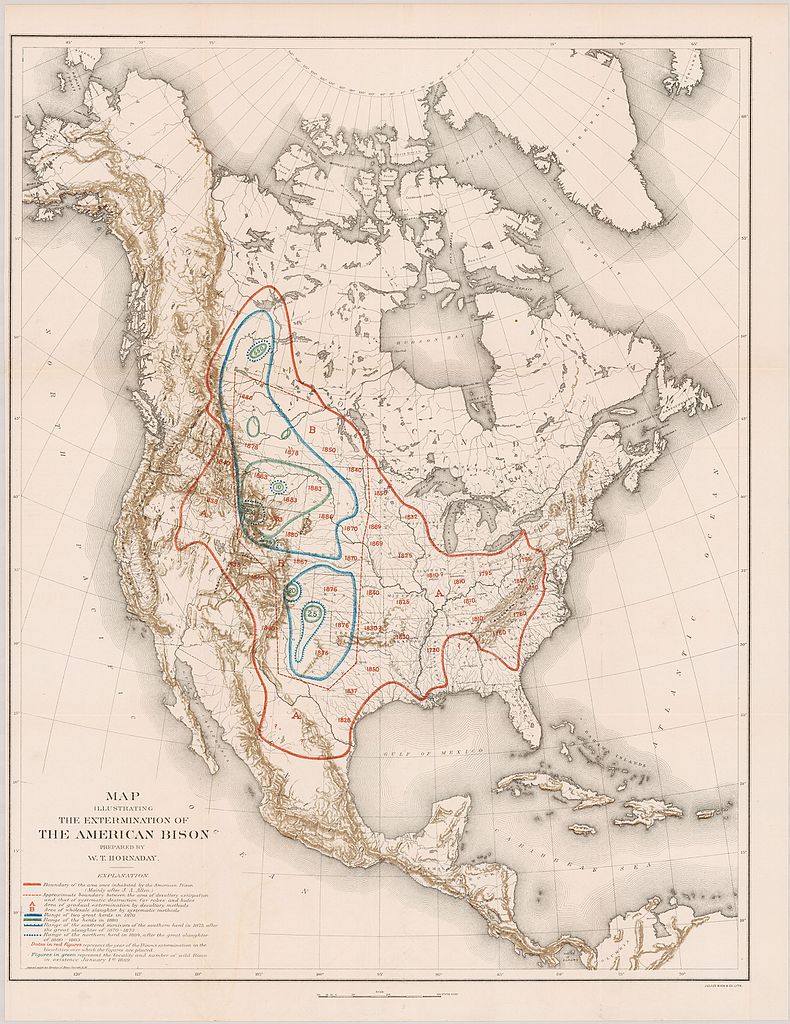

Still, from my digging, I discovered a few different maps and other folklore discussion of bison as far east as Pennsylvania. Two such maps, one from the Kentucky Geological Survey report of 1876 and another from 1889 under the direction of the Smithsonian (below), seemed to suggest that the 18th century distribution of bison surely had included Pennsylvania. I also found an early twentieth century collection of Pennsylvania folk stories about our wildlife, and the collection included bison. To be clear, I love both old maps and local folklore; however, this was all anecdotal without actual physical evidence of the animals’ presence.

My next step in the quest for answers was to explore the Smithsonian’s collection – from my computer here in Pittsburgh. The Smithsonian has most, if not all, of their collections listed online , and you can search their databases for the most interesting specimens and artifacts — most of which are not on exhibit. It’s truly a national treasure! I was able to search through all of their bison records: all of the skeletons, skulls, horns, teeth, and even the preserved parasites found in bison. Yet nothing from their exceptionally extensive collection represented evidence of a single bison found in Pennsylvania.

Now truly perplexed, I contacted a few of our own local Pittsburgh treasures: the curators and collection managers at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Suzanne McLaren, the chair of collections at the museum, shed a bit of light on this mystery. I asked her about the old stories of bison that seemed to have perpetuated the idea of their presence:

“Much of it was written by a man named Henry W. Shoemaker who was at some point named the PA State Folklorist,” Suzanne said. “Most was based on the notion that there are place names in the Commonwealth with buffalo in the name, such as Buffalo Township, etc.”

That explains the bison stories! What about the references to possible bison skeletons or remnants? I had been unable to find evidence of them, but surely someone else did?

“There was an early paleontologist named Cope who decreed that there were bison as far east as Philadelphia, based on some bones that were dug up near that city – and then he promptly discarded them.” Sue explained. “John Guilday, who was a paleontologist at Carnegie Museum from the 1950s to the 1980s, wrote about the matter of bison in PA, in which he casts doubt on that possibility…Guilday believed, and we concurred that Cope had looked at bones from cattle not bison.”

Considering the variety of cattle breeds, this wouldn’t particularly be a leap. Did other museums have any evidence of Pennsylvania bison, perhaps?

“Since we published our paper {doubting bison in Pennsylvania}, several people have re-started the search for any PA bison bones or horns (the latter quite unlikely to have survived), in any collection, including the Smithsonian, Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, and other institutions. None have any such material.”

Well, it seems my search has come to a close. On the one hand, I am reminded of one of my old professors who liked to note that the absence of evidence was not necessarily evidence of absence. However, it would seem that at this particular moment, there is little evidence to support the idea of bison in Pennsylvania. Thinking more broadly, Western Pennsylvania doesn’t even have the kind of habitat that a large, grazing herd animal would need (our close, hilly woods versus open meadow lands).

What I truly enjoyed from this mystery, though, was taking advantage of the resources available for online research at home. So many of yesteryear’s maps have been digitized, many museums allow you to search their collections online, and libraries are still an important community treasure trove of both digitized books and historic hard copies that remain in the physical building. Research can be a fun, exciting exploration for kids and whole families! Keep in mind whether your sources are trustworthy, and have fun exploring our world!

Special thanks to Dr. John Wible and Suzanne McLaren of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History for the role in solving this mystery!

Photo Credits: USDA CC0 (bison), Tony Hisgett CC-BY-2.0 (plains), William T. Hornaday under the Smithsonian CC0 (map)