Blog

#bioPGH Blog: Tree Rings to Rule them All

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

With tree limbs currently looking bare and wintry, it’s hard to imagine that something interesting is happening with our trees right now; but have you ever counted the rings on a tree? For those of us in temperate climates, we can think of this time of year as being an important part of why those rings are there. Let’s explore!

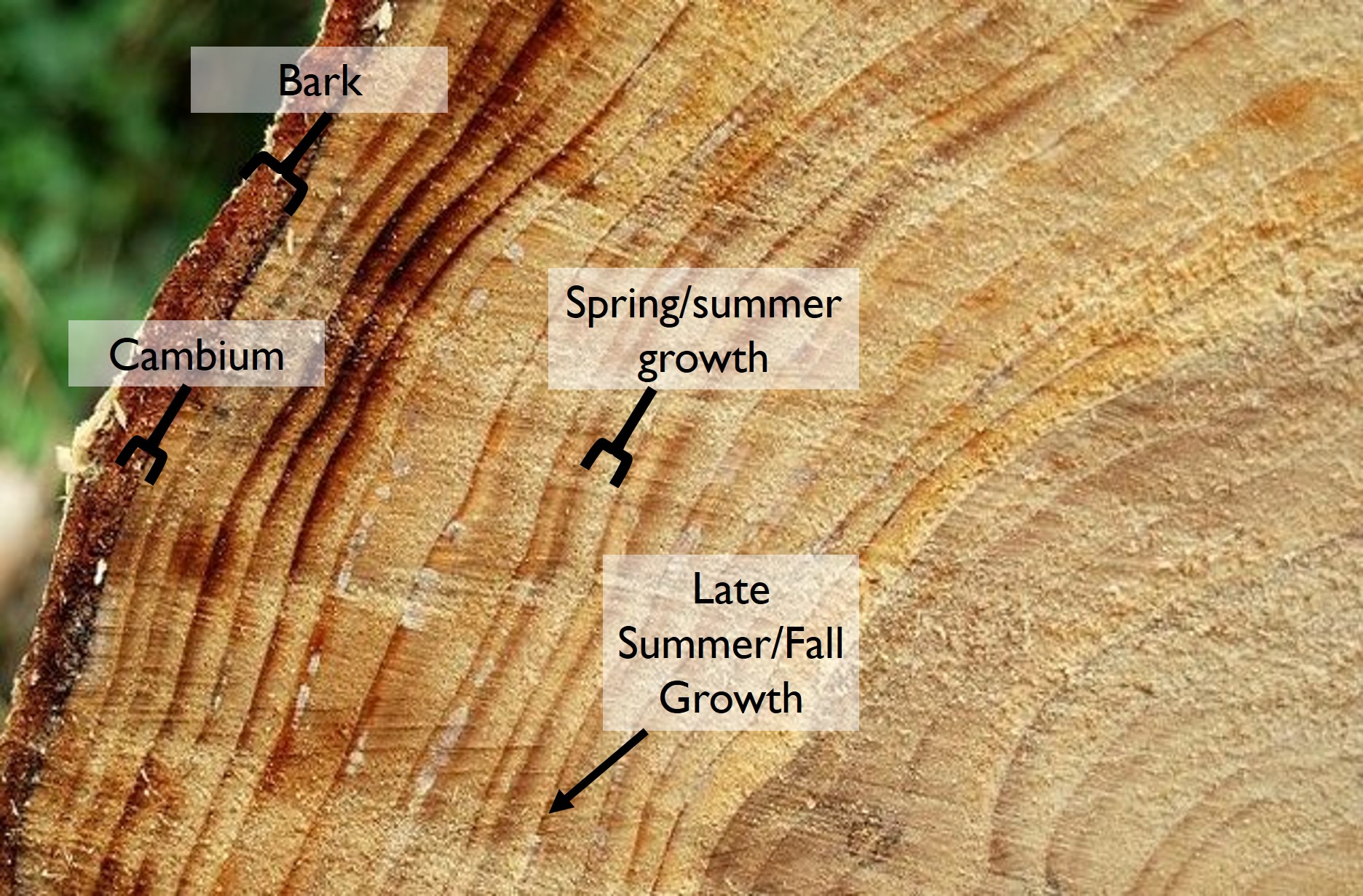

Broadly speaking, each full ring of a tree (the combined light and dark portions of the ring) shows a two different periods of growth. In our temperate climate, the lighter part of the ring shows the growth of spring and summer while the darker part of the ring shows the growth of late summer and fall of that same year. The wood of late summer/fall growth is much more dense than spring growth, which is why the color is darker. Our winters halt that growth, giving us a clear stop in the rings, and in the spring, trees will begin growing a new annual ring. In tropical climates, tree rings denote the timing of wet and dry seasons. Additionally, years of extreme weather in any climate can disrupt normal ring development.

Modified from Albert Bridge, CC-BY-SA-2.0

If we want to really dive into tree ring formation, though, we have to use a few technical terms. If you dig back to the plant science days of biology class, you may recall the terms xylem and phloem. Xylem is the plant tissue involved in distributing water and dissolved materials throughout the plant while phloem is the tissue that transports bulkier materials like sugars. In trees, xylem cells ultimately form the bulk of what we call wood. Then there is the cambium, a layer of growing tissue just under the bark from which new cells develop and break away — if you’re a quarantine baker, we can think of cambium as something like a sourdough starter. New xylem and phloem cells will break away from their “starter” cambium and grow up to be their own cells (like new little sourdough loaves!)

The whole process of tree ring formation is really all about xylem cell formation. This handy crash-course paper on tree ring formation summarized that the process of xylem formation can be described as five distinct steps:

1.) Cell Division – “Mother cells” in the cambium divide to form those new xylem cells — like a sourdough starter being split to make a new loaf of bread.

2.) The New Cells Grow Larger – Through a combination of complex cellular processes, new cells take on more water and nutrients to grow larger after they initially break away from the cambium. If we stick with the sourdough analogy, this could loosely be like adding flour and water to your batch, then letting the dough rise before baking!

3) The New Cells Get an Extra Cell Wall – Plant cells are different from animal cells in a number of ways, including a cell wall all around the outside. This wall is made of a tough sugar called cellulose and helps plant cells stay rigid. In trees, the xylem cells that will go on to become wood get an extra cell wall. This wall is quite different than the cellulose; it’s more like scaffolding to hold the next key component of wood.

4) The Cells are “Lignified” – Think of this part as the dough baking and becoming hard and crusty. Wood is a tough material because of a compound called lignin. Lignin fills in the spaces of that extra cell wall making the xylem cells tough and rigid like…wood!

5) The New Wood Cells Die – There are different kinds of xylem cells that make up the woody portion of trees and shrubs, and many of them die shortly after this process. However, they function as water and mineral transport even after the cells have died. (Notably, in a cross section of a tree, like below, sapwood still has active living cells, while heartwood does not.)

Modified from Biswarup Ganguly CC-BY-3.0,

Each year this process cycles through giving us new tree rings dependent upon the growing season. So even while it seems that our trees are quiet, once the next growing season starts, so will the formation of a new set of annual rings! Tree rings are also quite important to scientists from different fields, but don’t worry! Trees don’t have to be cut down to look at the rings. Researchers can drill thin cores to minimize damage to trees and leave forests intact. Fascinating, isn’t it?

Connecting to the Outdoors Tip: To explore year-to-year variations in how tree rings form, check out this online activity from UCAR Center for Science Education

Resources

Rathberger et al. 2016 – Biological Basis of Tree-Ring Formation: A Crash Course

NASA: Tree rings provide snapshots of Earth's past climate

Photo credits: Cover, Pixabay; Header, Pexels; Wikimedia user Biswarup Ganguly CC-BY-3.0; Wkimedia user Albert Bridge, CC-BY-SA-2.0