Blog

#bioPGH Blog: The Secrets of Skulls

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

In honor of this delightfully spooky day of Halloween, would you like to explore a little extra creepy biology? Let’s imagine you found…a skull. And you have no idea what it came from. That skull itself actually holds a number of secrets that can tell you quite a bit about the animal, even if you don’t know what it was. Let’s break down a few of these secrets, shall we?

Was Did this Animal Eat?

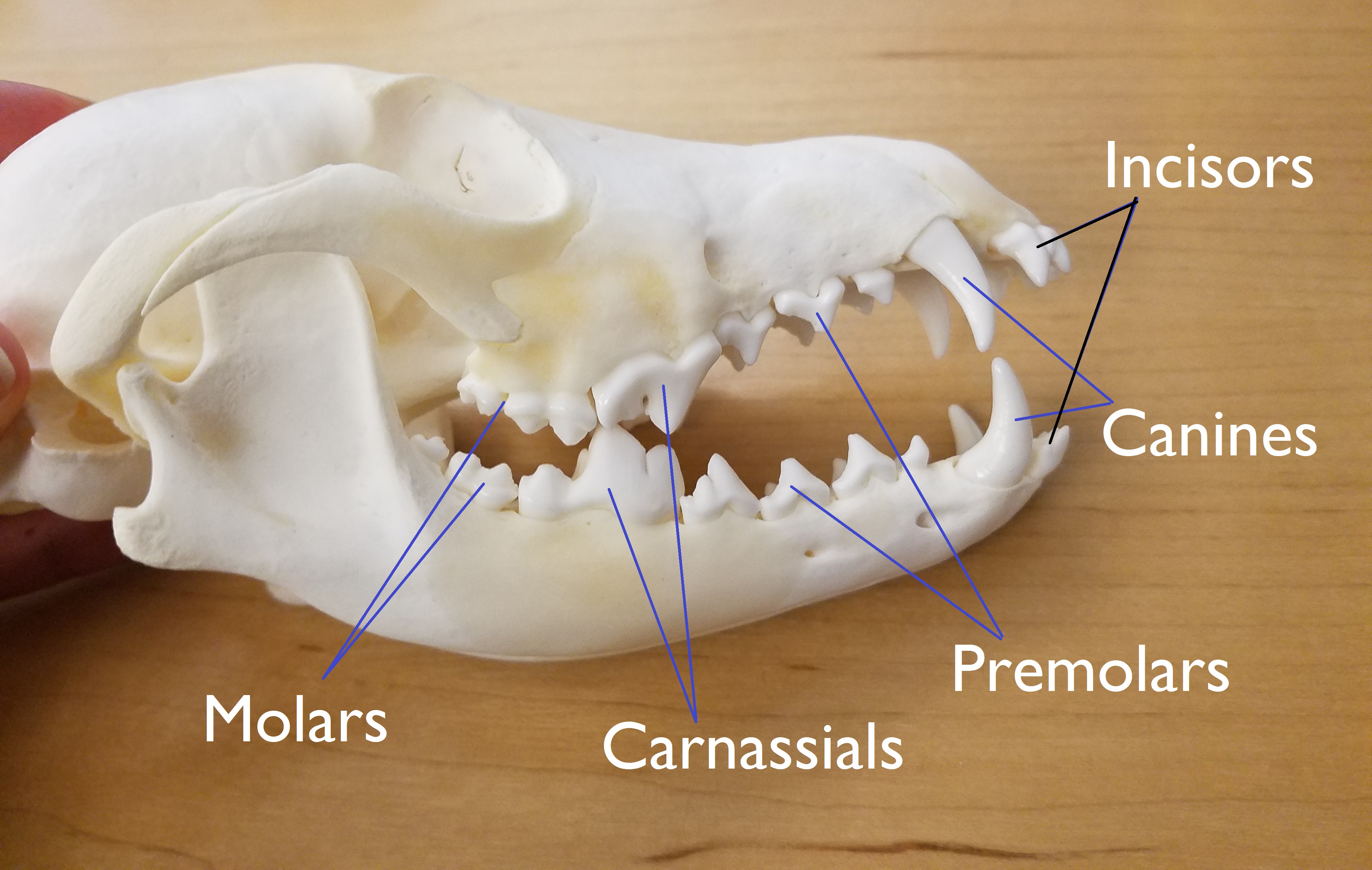

In the coyote skull model below, you can see the classic dentition (organization of teeth) of an animal that largely eats meat. The front incisors are flanked by elongated canines, and the premolars, molars, and carnassials are sharp and serrated for cutting through meat.

Animals that are more strictly herbivores generally have sharp incisors, no canines or canines that resemble incisors. They also have a space between their incisors and the next set of teeth (this space is called a diastema) which allows them to more easily manipulate plant materials in preparation for chewing.

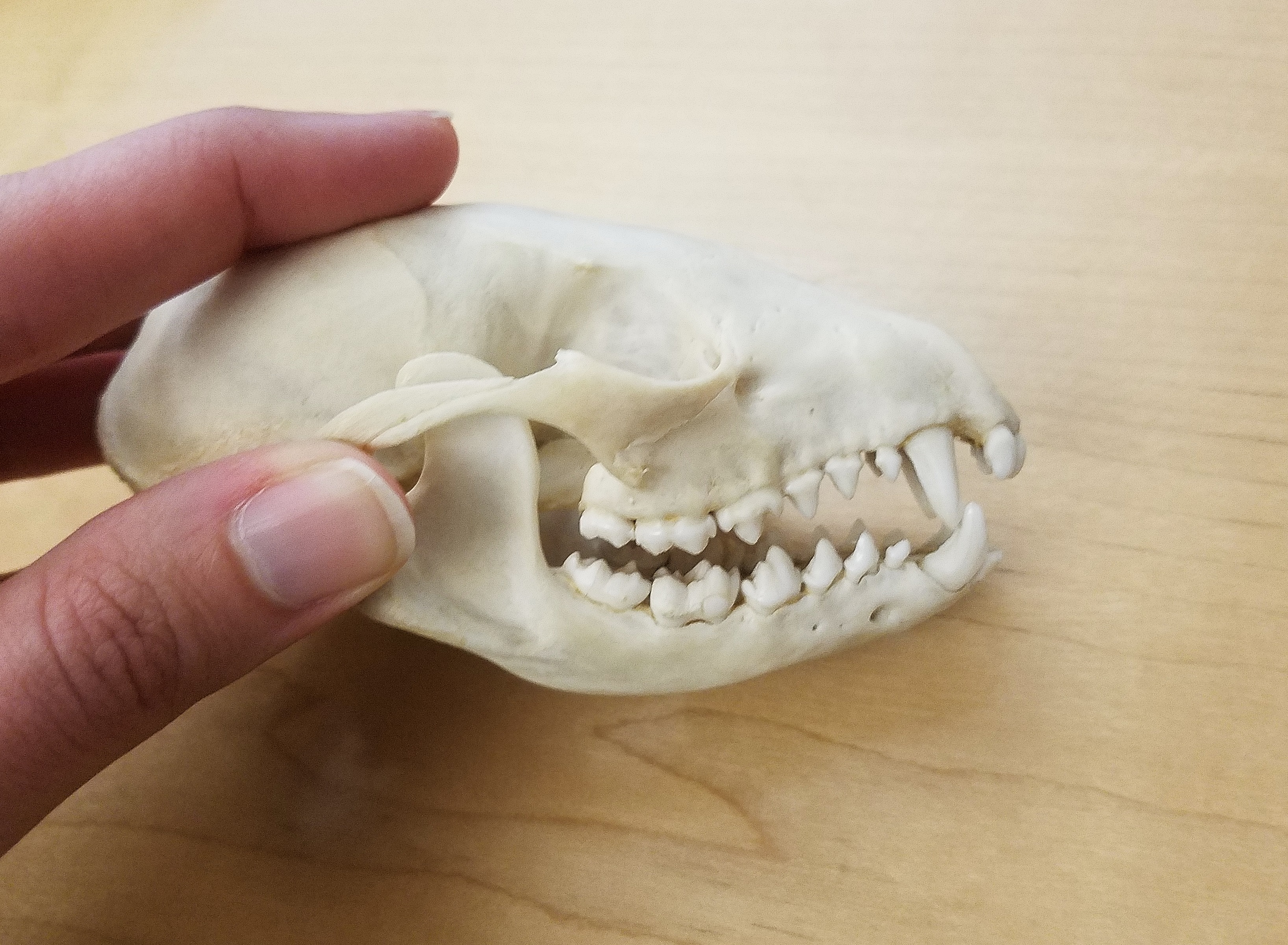

What about omnivores? Understandably, their teeth combine the traits of herbivore and omnivore dentition. They may have the pronounced canines and incisors of a carnivore but the molars and premolars more akin to an herbivore. The raccoon below is a good example!

How Strong Was This Animal’s Bite?

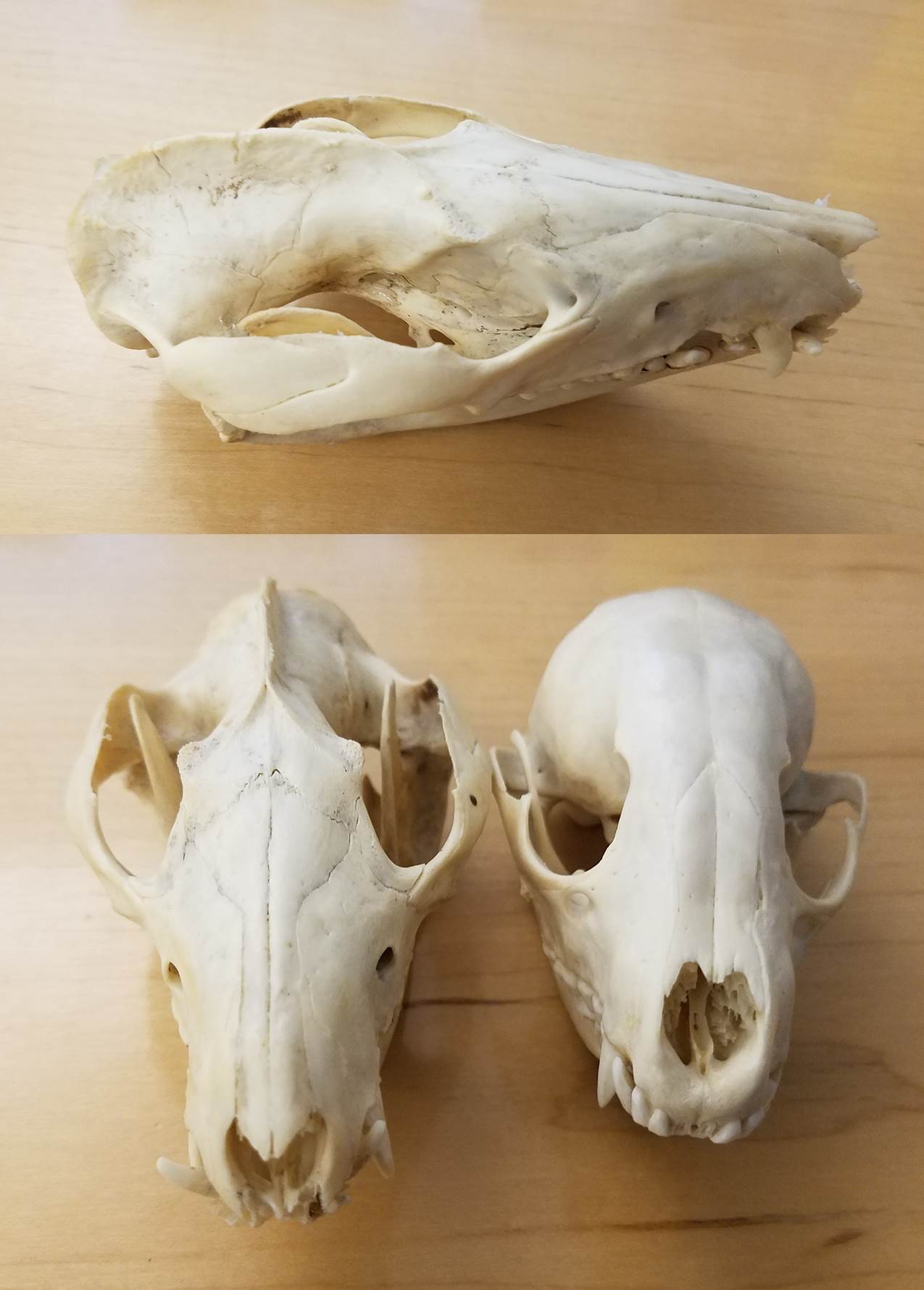

If you feel the top of your head, it should be relatively smooth and rounded. Some skulls, though, have a distinctly pronounced ridge that runs along of the top. This ridge is called a sagittal crest, and it’s a sign that the animal packs a load of power in its bite. The reason: the sole purpose of the crest is to hold extra muscle for the animal’s jaw. The picture below shows an opossum skull, complete with a sagittal crest (raccoon is the smooth skull for reference). Opossums have a bite strength of roughly 45 pounds per square inch. By comparison, the average human produces a bite force of approximately 160 pounds per square inch, but remember that little opossums only weigh an average 8-14 pounds! Of course, nature is full of exceptions; a few crocodilians have the most powerful bites in the animal kingdom and they lack a sagittal crest altogether!

Was This Animal a Predator or Prey species?

If you find a skull and you know nothing else about it, this helpful little rhyme will tell you something important:

Eyes on the side, I like to hide.

Picture a few predators—wolves, cougars, lions, tigers, humans—where are their eyes? If their eyes are in the direct front, like ours, the animal was likely a species who hunted. They may have been an omnivore, but predator eyes are directly in front to allow the animal to focus directly on a prey animal. On the other hand, prey animals have a greater need for wide-angled vision to spot predators from as many angles as possible. The trade-off is that a prey animal may not be able to see something a few inches directly in front of their face (think horses), but they are more likely to spot a predator long before it’s a problem.

Both photos public domain

When is this Animal Normally Awake?

A general rule of thumb is that animals with larger eyes are nocturnal, and their large eyes allow them to take advantage of even faint light sources.* If you look at a classic nocturnal animal, the owl, the eyes are a massive portion of their face. If we had eyes that were as proportionally large as an owl’s, we would have eyes the size of grapefruits.

*To avoid sounding misleading – another factor of nocturnal vision relies on cones and rods. Cones are microscopic structures in our eyes that detect color; rods are similarly microscopic structures that detect light. Many nocturnal animals have a higher density of rods than we humans do, which allows them see well in much lower light than us. This story doesn’t come through on a skull, but it’s important to note.

Well, now that we have chatted about skulls for a bit, it turns out they’re not actually spooky at all —they’re quite fascinating! So if you put out a decorative skull out for scares this evening, be sure to point out to somone the presence or absence of a sagittal crest and speculate on the associated bite force.

If you do come across a skull in the outdoors, it is best to leave it alone. Some parasites and wildlife diseases can transmit to either you or your pet, plus it’s always best to leave nature intact. The decomposers will love you for it!

Connecting to the Outdoors Tip: Pictures of skulls can be added to iNaturalist just like an entire animal! There are even some projects completely focused on skulls and bones, so data-collect away!

Continue the Conversation: Share your nature discoveries with our community by posting to Twitter and Instagram with hashtag #bioPGH, and R.S.V.P. to attend our next Biophilia: Pittsburgh meeting.

Resources

Skulls of Alaskan Mammals: Teacher's Guide

Penn State Extension: The Eyes Have It!

Photo credits: Header, public domain; all skull photos, Maria Wheeler-Dubas