Blog

#bioPGH Blog: The Plant Without Chlorophyll

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

What would you call a beach without sand? A coffee shop without a latte? What about a plant without chlorophyll? That one is easy—Indian pipe!

Doesn’t that sound strange, though? A plant with no chlorophyll means there is a plant that does not produce its own food via photosynthesis. Actually, there are approximately 3000 non-photosynthetic plants around the world! Rather than producing their own food, they can parasitize other plants or fungi. Here in Pennsylvania, the non-photosynthetic Indian pipe (Monotropa uniflora) looks practically eerie with its ghost-white flowers, leaves and scaly stem, though it’s in the same family as blueberries, snowberries, and rhododendrons. (Pennsylvania is actually home to a few different non-photosynthetic plants, but all of them—including the Indian pipe—are rare.)

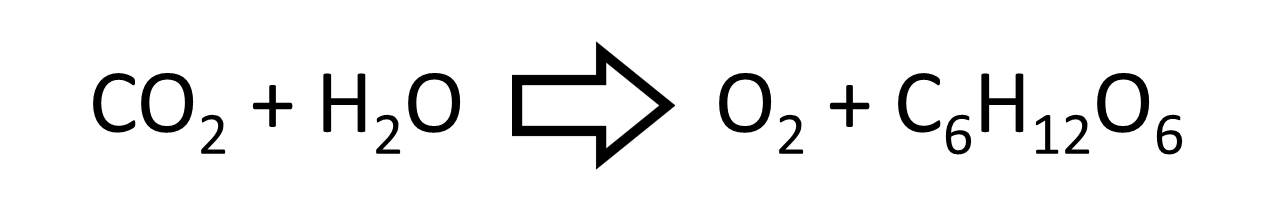

To completely appreciate how fascinating plants without chlorophyll really are, let’s take a closer look at the process that most plants use to produce usable energy: photosynthesis. The overall chemical process behind photosynthesis involves a plant converting carbon dioxide and water into breathable oxygen (O2) and a sugar— the last of which becomes the plant’s energy source. You may remember the simplified equation below from your most recent trivia night or your textbook days!

An important part to remember is that the process happens within a plant-specific organelle called a chloroplast. What’s an organelle? An organelle is literally a “little organ;” it’s a tiny working feature within a cell. Under a microscope, chloroplasts can be seen as little green flecks within their home cell, and their color comes from the plant pigment chlorophyll. It is chlorophyll, within a chloroplast, that initiates photosynthesis once it has been “excited” by a photon of sunlight.

The intriguing bit is that Indian pipe still has chloroplasts, but it lacks chlorophyll.

Without the chlorophyll, Indian pipe gets its nutrients from specialized fungi that typically associate with tree roots. It is a complicated process, but in summary: the fungal hyphae (think of them as fungus roots) invade the tissue of tree roots to find carbon sources like sugar. It actually works out beneficially for the tree, though. In return for some sugars, the tree receives nutrients from the fungi that are otherwise hard to come by; thus, it’s a beneficial relationship. This is where the Indian pipe comes in. The roots of the Indian pipe reach into the network of tree roots and fungi, where those same fungal hyphae reach into the Indian pipe roots. The Indian pipe absorbs nutrients from the fungi, but it can’t offer any sugars in return like the trees can. Thus, the Indian pipe is a parasite on the fungi. It is also important to note that the Indian pipe only ever forms connections with the fungi, never the tree roots. Altogether, this means you are most likely to find Indian pipe at the base of a tree. And because Indian pipe doesn’t need the sun, it can survive in on the heavily shaded ground of deciduous forests.

If you like investigating a good mystery, here is something else you will like about Indian pipe and other non-photosynthetic plants: they are wide open for study. As fascinating as they are, they are underrepresented in the scientific literature. This means that if you are a student intrigued by unanswered questions, studying non-photosynthetic plants might be just the path for you!

Connecting to the Outdoors Tip: Indian pipe can grow any time between May and October, you just have to be in a healthy older forest. According to iNaturalist (www.inaturalist.org), there have even been a number of observations of it in Allegheny County this summer, including at Frick Park! They are difficult to find, but even harder to grow in human care. If you do happen to spot one, take pictures and enjoy, but be sure to leave it as a something exciting for the next hiker.

Photo Credits: Wikimedia Commons user Liz West CC-BY-2.0 and Dennis Zastanceanu CC-BY-SA-4.0

Resources

Halling 2001: Ectomycorrhizae: Coevolution, Significance, and Biogeography

University of Virginia Mountain Lake Biological Station: Indian Pipe

Cullings 1996: Single phylogenetic origin of ericoid mycorrhizae within the Ericaceae