Phipps Stories

#bioPGH Blog: Of Monarchs and Milkweeds

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

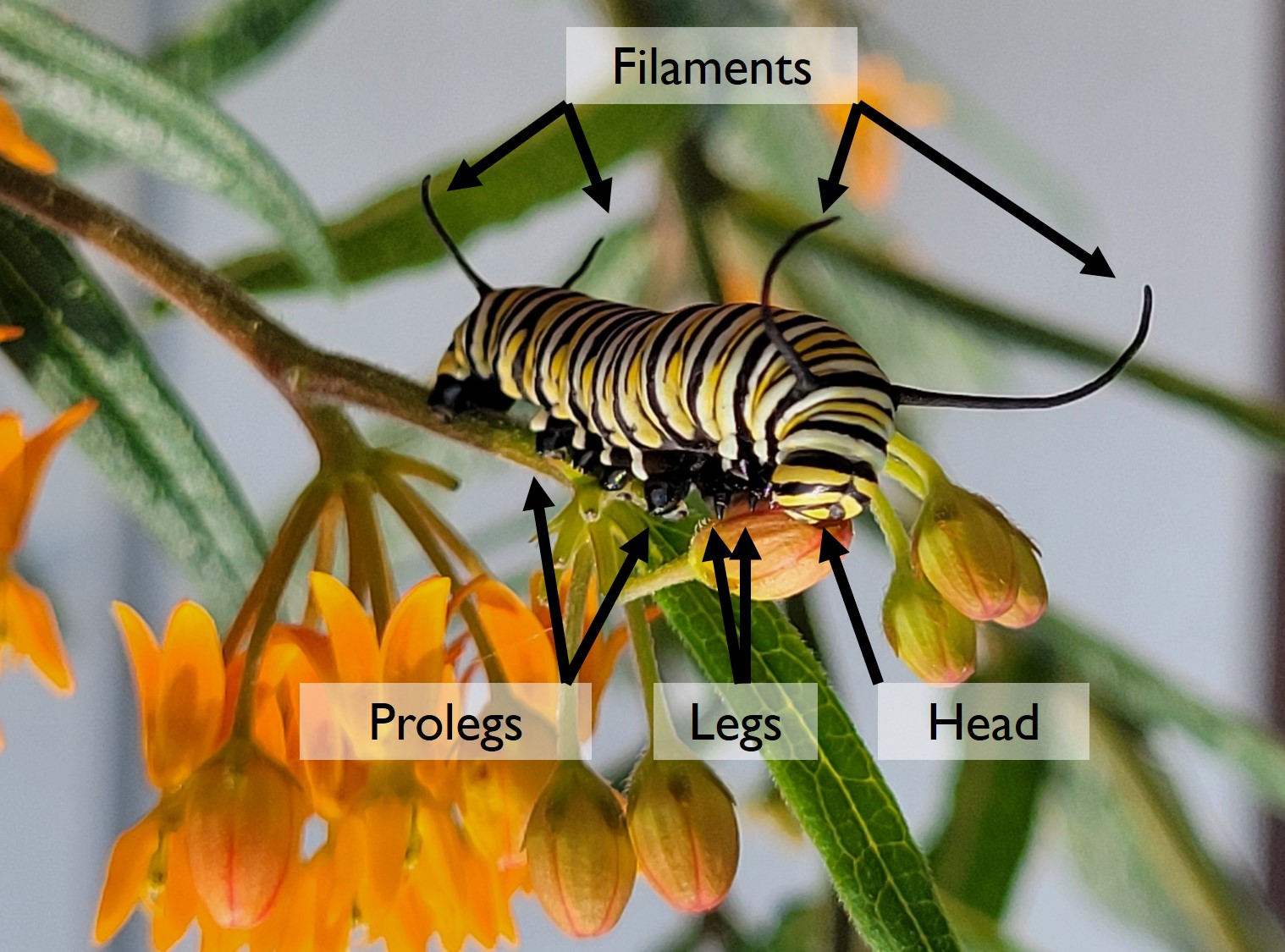

Sunday evening in the backyard, we spotted the first one. The distinctive stripes, the elongated filaments extending from segments at the far ends of the body, the characteristic om-nom-nom on the leaves — monarch butterfly caterpillars. By the next evening, we had spotted two more!

A fascinating little friend who isn’t always what he seems.

All three of our caterpillars were found on the leaves of an important plant: butterfly weed (Asclepius tuberosa). Butterfly weed is a type of milkweed, and milkweeds are essential in the life cycle of a monarch butterflies. Females lay their eggs on milkweed plants, and the caterpillars feed exclusively on their leaves. Milkweeds produce toxins called cardenolides, which can interfere with the way cells reset after electrical activity, such as nerve impulses. Due to a few unique proteins, monarch caterpillars are able to consume cardenolides without any adverse effect — but even better, it provides a layer of protection from predators as the caterpillars themselves become toxic from their diet. And if the appetites on these three are any indication, I’m sure they are quite toxic to predators by now!

Caterpillars certainly need plenty of nourishment in this stage before they begin their energetically-costly metamorphosis to become an adult! Then as adults, monarch butterflies take part in an epic migration from Canada and the US down to Mexico and back up. This migration is so epic, in fact, that no single generation completes the entire route. For our monarch butterflies in the eastern US, caterpillars like the ones we are seeing now at this point in the summer will become adults just in time to begin migrating to Mexico where they will over-winter in huge colonies with other migrants. In March, they will begin traveling northward, but will pause to produce the generation that will continue northward — it actually may take 2-3 new generations to disperse throughout eastern North America! (Out west, the migration patterns look a bit different.)

Presumably then, if these three little caterpillars in our backyard all grow to adulthood, they will probably be the generation to begin the grueling journey back to wintering in Mexico. How cool is it that we get to support this stage in such a remarkable life history? And this is just our first year with this new butterfly weed in our yard! If you’re interested in playing host to monarchs as well, look into native species of milkweeds (members of the Asclepius genus). There are a few things to be careful to avoid, though. For example, we have butterfly weed planted, but there is a similarly-named butterfly bush in the genus Buddleia that is often suggested as a pollinator garden fixture because it has bright colors and does indeed attract pollinator. However, our native caterpillars cannot eat its leaves, and it often outcompetes our native species that are important food sources. So be sure to opt for butterfly weed and avoid butterfly bush. Similarly, as the climate has been changing, a few tropical species of milkweed have started gaining popularity in the US, as they are showier and tolerate heat well; however, again, these do not provide a proper food source for our caterpillars, making them useless to the butterfly population long term. So opt for native milkweeds! If you’re unsure, check out our list of suggested plant nurseries, and happy planting!

Milkweed next to the Center for Sustainable Landscapes

Connecting to the Outdoors Tip: Keep an eye on various milkweed plants to spy caterpillars, but when they form a chrysalis, also keep an eye on plants up to 20-30 feet way. Caterpillars may form a chrysallis on milkweeds, but they have often stripped the leaves, which could leave them too exposed in a vulnerable state.

Continue the Conversation: Share your nature discoveries with our community by posting to Twitter and Instagram with hashtag #bioPGH, and R.S.V.P. to attend our next Biophilia: Pittsburgh meeting.

All photos by Maria Wheeler-Dubas

Resources

Scientific American - How Monarch Butterflies Evolved to Eat a Poisonous Plant

Scientific American - Planting Milkweed for Monarchs? Make Sure It's Native

Scientific American - Study on Weed Killers and Monarch Butterflies Spurs Ecological Flap