Phipps Stories

#bioPGH Blog: Not-So-Spooky…Bats!

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

In honor of this week’s spooky holiday, I wanted to focus on critters some folks find spooky — bats! Oh, how they can make some of us shiver! The truth is, though, bats are excellent creatures to have about. They save the US approximately $3.7 billion in annual pest control costs, some disperse seeds, and some are pollinators. There are quite a few myths about them out there and exaggerations about some habits, but overall they are an amazing group of animals. Let’s check out this absurdly adorable video of a baby flying fox (large bat) and then explore our own Pennsylvania bats!

Did that adorable little one from Australia change your mind? Excellent! We have nine species of bats here in Pennsylvania:

- Little Brown Bat (Myotis lucifugus)

- Northern Long-Eared Bat (Myotis septentrionalis)

- Indiana Bat (Myotis sodalis)

- Small-Footed Bat (Myotis leibii)

- Silver-Haired Bat (Lasionycteris noctivagans)

- Tri-colored Bat (Perimyotis subflavus)

- Big Brown Bat (Eptesicus fuscus)

- Red Bat (Lasiurus borealis)

- Hoary Bat (Lasiurus cinereus)

Bats are often feared for their association with vampires, but of the roughly 1400 species of bats in the world, though, only three South American species of vampire bats gave rise to notorious legends that strike Transylvanian fear into our Halloween parties and nighttime walks. The majority of bats across the planet — including all of our Pennsylvania bats — are insectivores, meaning if you don’t like mosquitoes, you’ll love bats! Of the remaining species, a few hunt small prey, but many species of bats are largely frugivores, or fruit-eaters.

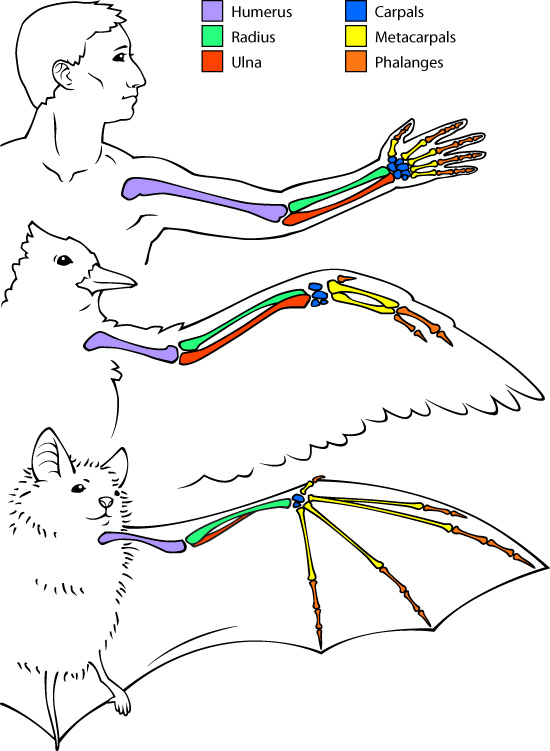

Their pest-management prowess is admirable, but bats are also known for their aerial abilities. In fact, though some animals like flying squirrels and lemurs can “glide” through the air, bats are the only mammals capable of true flight. They accomplish this in a slightly different way than birds, though. If you look at the skeletons of birds versus bats, you’ll notice both some overlap and some differences. For example, you can see in the image below that birds and bats share structures similar to humans and indeed many other animals. The three of us share similar arms bones in the humerus, radius and ulna, but some differences arise after that. For us humans, an assortment of small bones make up our hands and fingers: the carpals, metacarpals and phalanges. In a bird wing, many of those small bones are fused together, or they are short and comparatively stocky. In bats, though, their “hands and fingers” are rather extensive, with their “fingers” making up nearly half of a bat wing (although this varies by species).

Image © Arizona Board of Regents / ASU Ask A Biologist, CC BY-SA 3.0

Another fascinating angle of bat biology is their ability to use echolocation, or bouncing sound off their surrounding environment to “see” their world. Intriguingly, bats must be able to balance out acoustic information they are receiving about larger and more distant features in their environment (e.g. trees, buildings, etc.) while also gathering formation about the smaller, quickly moving diet items are searching for — after all, there is a lag time while sound is bouncing back from faraway structures, but bats need to call again as quickly as possible to hear objects in rapid motion, like flying insects. To manage this, some bat species will alter the intervals between their calls, depending on how “cluttered” the environment is, to ensure they are receiving up-to-date information about the dark nighttime world around them. Different bats can also carefully manage the pitch of their calls to maximize the efficiency and precision of their travels, like in this fun (and delightfully quirky) video below:

Bats do face an alarming conservation threat, though. White-nose syndrome is a fungal disease that has devastated many North American species of bats, including our own Pennsylvania populations. It infects bats when they are overwintering in caves, and it causes an increase in bat activity and metabolism that far outpaces normal hibernation activity, which severely weakens or kills the sick bats. The origins of this disease are unknown, but US Fish and Wildlife is coordinating the massive effort to manage it. Check out the video below from the Pennsylvania Game Commission as they monitor hibernating bats in northern PA, and if you’re interested in doing more, the national response website has some resources on how we all can help bats.

Connecting to the Outdoors Tip: As the temperatures drop, our bats will either begin hibernating or have already migrated to warmer locales; but on warmer days, keep an eye out for a bat (like the Eastern red bat) that may be temporarily awakened by a warm streak.