Blog

#bioPGH Blog: Maybe a Mastodon Snack?

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

When I think of mulberry trees, I think of the little purple berries that grow on the tree on my backyard — if I’m not quick, the birds will beat me to the lower branches! I don’t, however, generally think of a softball-size mass of solid green with brainy squiggles all over it, but a curious member of the mulberry family is the Osage orange tree (Maclura pomifera). Osage oranges, also known as hedge apples or monkey balls, aren’t the most common tree in Western Pennsylvania, but like the ginkgos we talked about a few weeks ago, Osage oranges are something of a living memory. Let’s take a dive into biology and history, shall we?

Osage orange leaves, H. Zell CC-BY-SA-3.0

Osage orange trees are generally 40 – 60 feet tall, with elongated lance-shaped leaves. The species is diecious, with separate male and female trees, and the “female trees” produce those distinctive, large green fruits in October-November. Though green and brainy from the outside, the inside of the fruit has a texture comparable to pineapples and contains a latex sap as well as a few compounds that make them unpalatable — and possibly harmful — to some humans.

The fruits cut in half.

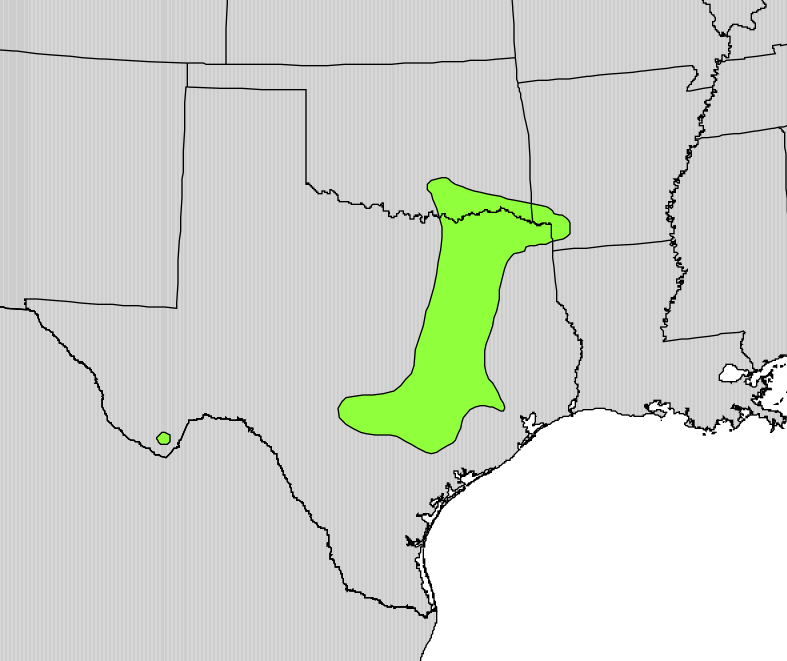

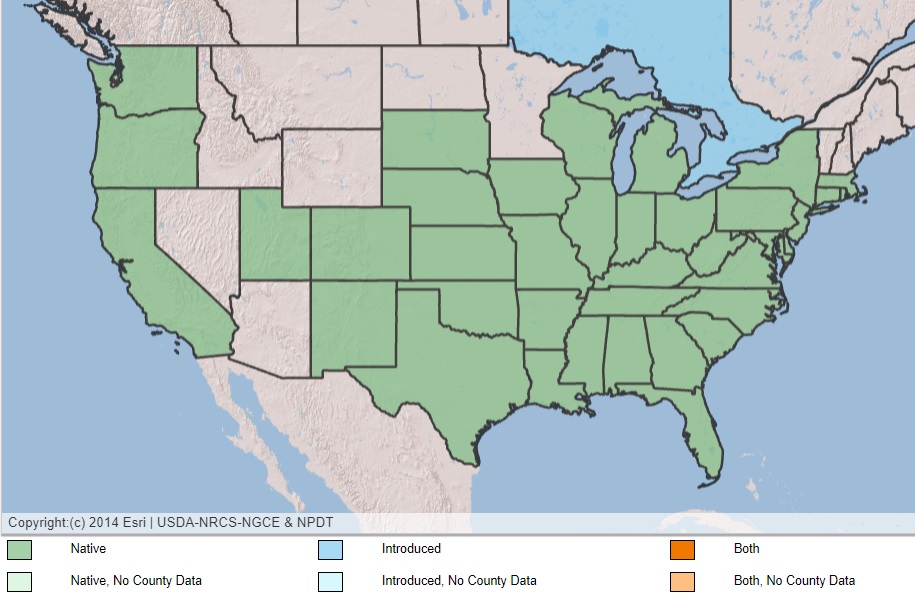

The trees may have been originally native to the Midwest and southern central states, like Texas and Oklahoma; but the tree can currently be found across most of the Lower 48 states.

Theorized Pre-Columbian distribution of Osage orange trees. Map from USGS.

Current distribution of Osage orange trees. Map from USDA.

An interesting question about this tree is: Why the huge fruit? Wildlife tend not to prefer the hedge balls as a primary food source. Some animals will eat them when necessary, but no species in particular is big enough to need a fruit that large and the latex juice is unpalatable to many animals (us included). However, a common hypothesis about Osage oranges is that they were the historic diet items of…mastodons!

Once upon a Pleistocene Epoch (2.5 million – 12,000 years ago), the US was home to incredible megafauna like huge ground sloths, giant armadillos, saber-tooth cats, camels, woolly mammoths (!) and their distant cousins the mastodons. Mastodons were browsers, preferring leaves and the tough vegetation of taller shrubs and trees, while woolly mammoths were grazers, eating low, shrubby plants and grasses near the ground. Mammoths had fairly flat teeth but mastodons have relatively pointy teeth for an herbivore, which would be perfect for chewing the oversized fruits of the Osage orange tree. A mastodon and Osage oranges would be the perfect pairing for seed dispersal, and then millennia later, humans would act as the primary seed disperser since we have so many uses for the tree’s wood.

Even though this does make quite a tidy idea, there are some counter-arguments to this hypothesis. One point is that the seeds of modern-day Osage orange seeds don’t seem to germinate well after passing through the digestive system of horses or even elephants, but they would certainly need to have been able to survive the gut of large herbivores historically. (This is not an automatic dealbreaker, I would assume — the gut microbial community of animals thousands of years ago may have been different and perhaps may have had a different impact on the seeds.) Another point is the issue of fruit size. Mastodons have been gone for thousands of years, yet the trees are still producing unnecessarily large fruits, which are energetically costly and seemingly have no modern pay-off if the size isn’t attracting the massive herbivores.

But whether or not we can say for sure that mastodons and other Pleistocene giants ate Osage oranges, we can indeed say they produce a delightfully wonky fruit — even with a brainy, bizarre theme to cap off Spooky Season. So enjoy the sight, and enjoy the fall weather outdoors!

An Osage orange? Or mitosis?

This one is literally half the size of my face!

Continue the Conversation: Share your nature discoveries with our community by posting to Twitter and Instagram with hashtag #bioPGH, and R.S.V.P. to attend our next Biophilia: Pittsburgh meeting.

Photo credits: Header, Pexels. All other images from Maria Wheeler-Dubas, unless otherwise noted.