Blog

#bioPGH Blog: Cicada Summer

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

Buckle up, Pittsburgh! Sometime in the next few weeks, we are going on a once-every-seventeen-years ride through an entomology wonderland: the cicadas are emerging. We all are probably familiar with annual cicadas (also called the “dog day” cicadas), but this summer will feature a group of cicadas that only come above ground for part of a single summer to breed, and their young will stay below ground for the next seventeen years. It’s a true delight for insect enthusiasts, and since cicadas can’t even bite or sting, the whole family can enjoy the sights (and sounds) of this infrequent event!

Cicadas are a group of insects in the “true bug family.” Even though they seem to superficially resemble locusts, they are actually not related to grasshoppers or locusts at all—they’re more closely related to stinkbugs.

Here in North America, we have several species of cicadas that have adapted to an unusual “periodical” life cycle that results in nymphs spending either thirteen or seventeen years underground. The nymphs survive those long years by tapping into tree roots with their piercing, sucking mouth parts, and they “drink” the nutrient-filled sap (xylem) of the tree. In the spring of an emergence year, the nymphs will begin creeping upwards in the soil to a depth of only an inch or two below the surface and wait for their cue to emerge—warm soil. Here in Western Pennsylvania, the means a ground temperature of approximately 65 degrees. Then, the cicadas will finally emerge aboveground, and they will spend their three to four weeks of adulthood finding mates and laying eggs. The storied circle of life continues with those eggs: new, young nymphs hatch after seven weeks, and they immediately go below ground, where they will stay for the next seventeen years.

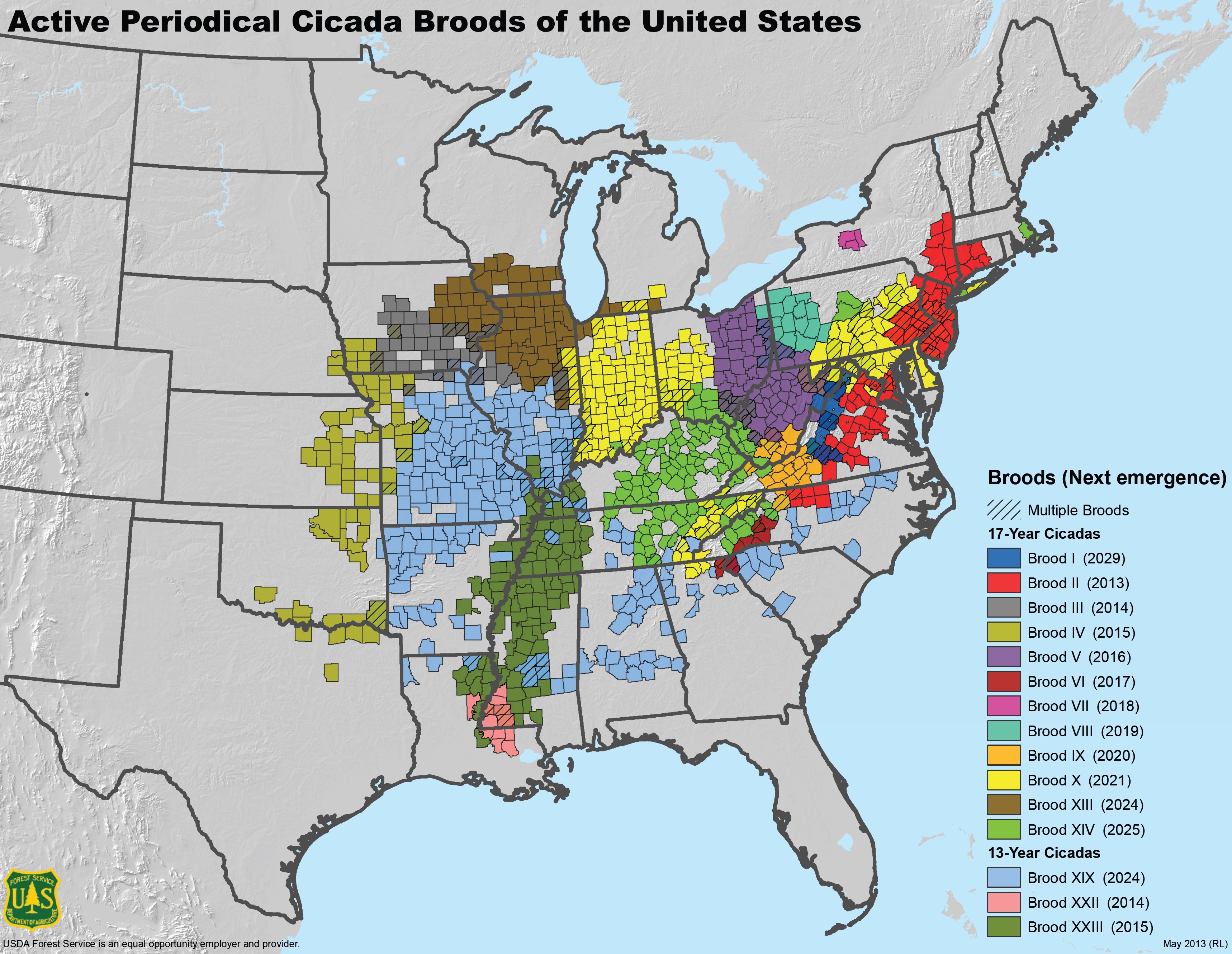

You have probably heard in the news that we will see “Brood VIII” emerging shortly. In the US, we have fifteen active periodical cicada broods in the US, as you can see in the map below. Each brood is a group of millions of individuals that may encompass multiple species who all live on the same “schedule.” Most broods are on a seventeen year cycle, though a few are on thirteen year schedules. Our brood in particular contains three different species and could emerge as early as mid-May!

USDA Forest Service, public domain

Though folks often have concerns about a large number of unusual insects appearing once, there really is little to worry about with cicadas. When they emerge, it would be fair to expect to hear their loud buzzing, but that is about the worst of it. They can’t bite or sting, and they aren’t poisonous or venomous. They also aren’t expected to do any serious damage to greenery in the area. Their goal as adults is to produce the next generation—dinner is a much lower priority for them. So just enjoy the rare occurrence!

Connecting to the Outdoors Tip: Since nymphs will need support from a mature tree for seventeen years, your best bet for seeing high densities of cicadas will be in parks or wooded areas - but you will likely encounter them across the region.

Continue the Conversation: Share your nature discoveries with our community by posting to Twitter and Instagram with hashtag #bioPGH, and R.S.V.P. to attend our next Biophilia: Pittsburgh meeting.

Resources

USFWS: Active Periodical Cicada Broods of the United States

Cooley and Marshal 2001: Sexual Signaling in Periodical Cicadas, Magicicada

Williams and Simon 1995: The Ecology, Behavior, and Evolution of Periodical Cicadas

TribLive: 17-year cicadas are coming already? Here’s why

KDKA Pittsburgh: Massive Brood Of Cicadas Expected In Southwestern Pennsylvania In Just Weeks

Photo credits: cover, Robert Webster, CC-BY-SA-4.0; Headers, Pexels