Phipps Stories

_747_390_s_c1.jpg)

#bioPGH Blog: Chipmunks

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

Occasionally, when I’m in my backyard in the early morning, I might hear the light chattering of birds interrupted by a harsher chip-chip-chip-chip-chip-chip. Though this sounds rather bird-like as well, it is actually the vocalization of chipmunks:

North America is home to 24 species of chipmunk, but here in western Pennsylvania, we are most likely to see the eastern chipmunk (Tamias striatus). They can be found primarily in forest habitat as far south as Florida and Mexico and as far north as Quebec in Canada; but they can also be quite at home in modified habitats like human neighborhoods. You have probably have seen plenty of these busy little omnivores gathering seeds, fruits, and nuts — and they may also nibble off carcasses, snatch a bird egg, or possibly even new hatchlings on occasion!

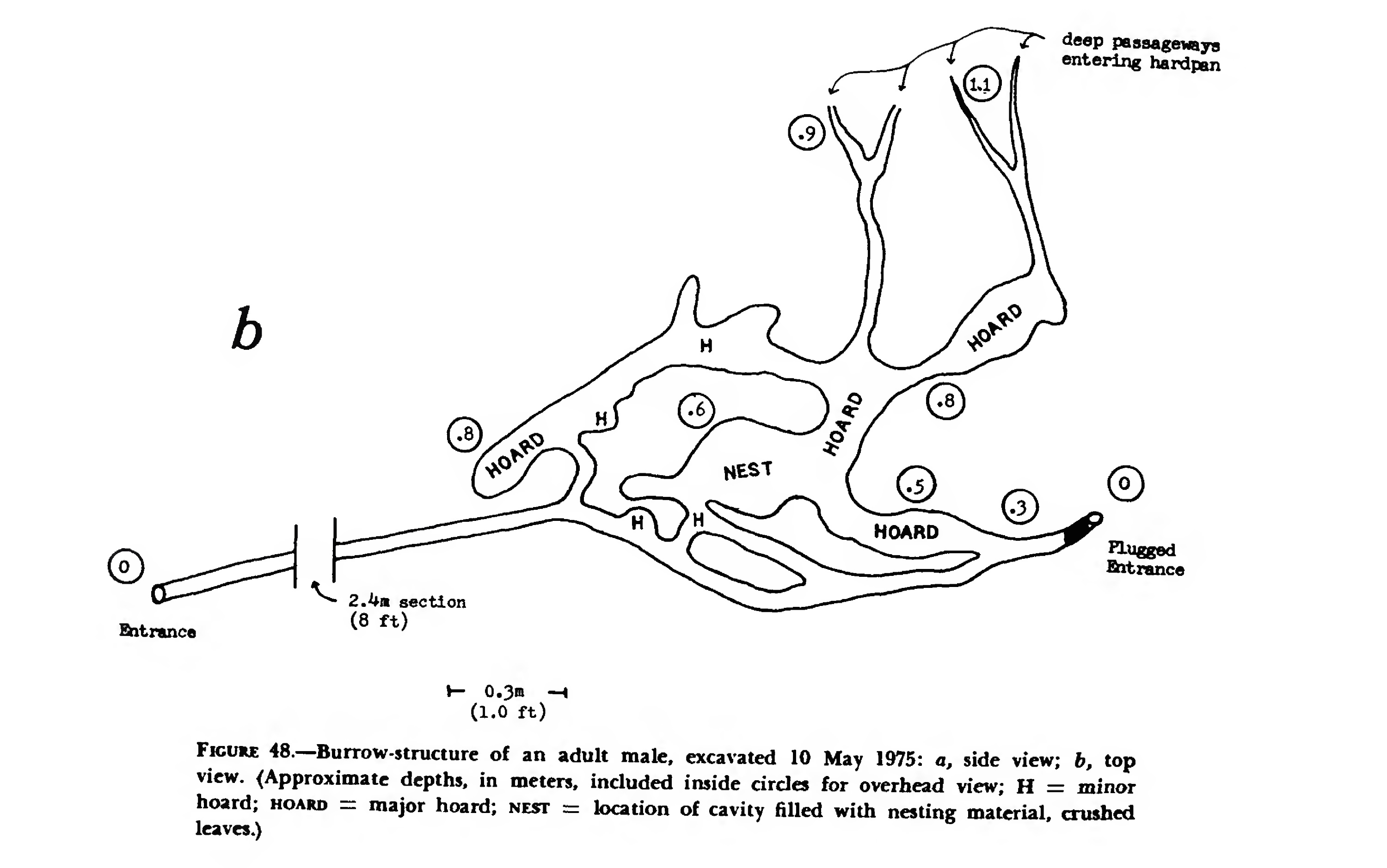

Though we may often spot chipmunks in trees, they are actually a burrowing animal and they are skilled little engineers. Their elaborate tunnel systems have areas for nesting, several gallery spaces for hoarding food, a “bathroom” for relieving themselves, plus a second entrance/exit that is usually stuffed closed with leaves.

Example of a chipmunk burrow. Smithsonian publication, Social Behavior and Foraging Ecology of the Eastern Chipmunk (Tamias striatus) in the Adirondack Mountains, Lang Elliott, 1978, Figure 48b, p84.

This burrow is very important for both young-rearing and torpor in the winter. In the spring and summer months, females may raise up to two broods of offspring, and the babies stay in the burrow until they are approximately eight weeks old and ready to start exploring the outside world. Then beginning in October or November, the burrows become a refuge for winter. Chipmunks don’t truly hibernate, but they make it through winter by going into torpor, a state of decreased metabolic activity, for 1-3 days at a time. They use the different chambers of their burrow to eat stashed food or defecate periodically throughout the coldest months.

As chipmunks are rodents, they are known to occasionally make “pests” of themselves via their prolific chewing and digging abilities. They may burrow under patios, dig up bulbs from gardens, and they have been known to chew wood, insulation, and home wiring — though that certainly doesn’t end any better for the chipmunk than the homeowner! Some suggestions for living peaceably alongside our wild neighbors include avoiding dense vegetation planted right up against your house as this can hide their burrow entrances, and install hardware cloth under garden areas or sensitive spaces near your house.

I will admit, especially as I note the ways they can make a nuisance of themselves, chipmunks are an animal I can easily take for granted. They are small, fairly common and harmless at best, mildly annoying at worst. I have to chuckle, though — I have worked in zoos and it never failed that I could point out a tiger to a six year old, and the kiddo would be equally impressed by the chipmunk next to the tiger habitat. Maybe it’s my extra decades, or maybe it’s the daily ho-hum of life, but I know I forget to just let myself embrace the wonder of my surroundings like those six year olds. I forget to find the magic in what we call the mundane. Perhaps we all could remind ourselves of that feeling of enchantment again — even when the object is something as “common” as a chipmunk!

Connecting to the Outdoors Tip: If you’d like to get involved in some community science focusing on chipmunks or other mammals, check out the Pennsylvania Mammal Atlas. As a volunteer, you can upload your PA mammal photography to the website to help document wildlife across the state!

Resources

National Geographic – Chipmunks

PA Game Commission – Chipmunks

Penn State Extension – Chipmunks

Photo credits: cover Wikimedia user Rhododendrites, CC-BY-SA-4.0; header, Pexels