Growth and Change (1930 – 1971)

Phipps' collection expanded in 1932 with the acquisition of the Armstrong Orchid Collection, consisting of 800 rare plants. This gift, valued at $50,000 and donated from the estate of Armstrong Cork Company President Charles D. Armstrong, propelled our Conservatory into the front ranks of premier botanical facilities.31 Also in 1932, the City of Pittsburgh initiated an agreement with the Carnegie Institute to incorporate steam heating at Phipps from the nearby Bellefield Boiler Plant just across the Schenley Bridge.32 Construction would not begin for some time, but this agreement marked the beginning of the evolution of Phipps’ energy infrastructure.

36

36

Phipps Conservatory, 1930s

Superintendent Moore retired from the Parks in 1934 after eight years of service with the Conservatory; professional landscape architect Ralph Griswold was promoted into the position after being hired by the City of Pittsburgh in 1933. Griswold hired Adolphe F. DeWerthe and Frank Curto as horticulturist and assistant horticulturist for Phipps. DeWerth, known as “Doc,” held a Master of Science degree from Ohio State University specializing in tropical plants. DeWerth and Griswold combined their talents in organizing an entirely new idea in flower show arrangement: Rather than displaying rows of potted plants, each room would have a central idea in which the flowers blended to form a pattern. These themed gardens were the genesis of our Conservatory’s now-iconic storytelling flower shows.

37

37

Fall Flower Show, 1932

The mid-to-late 1930s brought thrilling changes to Phipps. The first iteration of our capital campaigns developed in 1935, when Johanna Hailman organized the Pittsburgh Parks and Playground Society. Its initial purpose was to head a campaign to renovate the Conservatory building and rebuild the plant collections. The Society’s first project was extraordinarily beneficial to Phipps, funding the installation of lighting to allow the public to visit the glasshouses at night. This led to the first-ever admission charge to enter the Conservatory. During evening hours, admission cost 25 cents for adults and 10 cents for children. In spring of 1935 the Society facilitated the repainting of all interiors, remodeling of Palm Court and reorganizing of plant arrangements prior to the April opening of the next Spring Flower Show. This partnership also sponsored various new gardens: A Cloister Garden (now known as the Broderie Room) contributed by the Garden Club of Allegheny County; a Pennsylvania garden with plants native to the state gifted by the Parks Commission; and a rose garden and modern garden sponsored by various donors. The Pittsburgh Parks and Playground Society also contributed to special tropical and semi-tropical plant exhibits later in the year.33

Spring Flower Show, 1937

Despite these exciting developments, the Conservatory was in great need of larger renovations. In April 1936, 100 workmen from the Works Progress Administration (WPA) completed a Conservatory modernization program. The South Conservatory as we know it today was formed with the addition of partitions in the Economic Room which divided it into three distinct galleries. A brick wall and doorways were added to create a non-public walkway leading to the greenhouses. Superintendent Griswold designed a Perennial Garden to replace the lawn sloping down to the Schenley Bridge from the west side of the Conservatory with funds and the work force provided by the WPA; this space would subsequently evolve into what is now our Outdoor Garden, and hardscaping from the WPA project is still visible within.

On Feb. 21, 1937, the new renovations to Phipps were jeopardized by a storm producing winds up to 60 miles per hour, which whipped snow and hail through Pittsburgh. Phipps withstood the brunt of the storm, taking significant damage — part of the roof ripped from the building and large panes of glass shattered, forcing the removal of the crowning ogee on Palm Court, which wouldn't be restored until 2018. Tropical plants were exposed to frigid temperatures of 30°F. With the clock ticking to save the expensive exotic plants, firefighters and police worked through the night to cover them with improvised canvas “blankets.” Superintendent Griswold estimated the financial loss at $20,000.34

Director of Pittsburgh Public Works Frank M. Roessing was placed in charge of the Conservatory’s repair. He organized 200 WPA workers to hastily restore structural integrity to the glasshouses.35 The Spring Flower Show opened without delay on March 28 and was the first show to display DeWerth and Griswold’s new “garden plan” with a theme for each room, rather than the waist-high rows of potted plants. After the show concluded, Phipps closed its doors for extensive renovations. The storm damage had revealed that the aging structure of the Conservatory was badly eroded.36

Roessing once again took charge of restoring the now 40-year-old conservatory; the antiquated steel had “rusted away to nothing” and the task of replacing it proved slow, with obstacles arising at every development. The upcoming Fall and Spring Flower Shows were moved to the Phipps Conservatory in West Park (formerly part of Allegheny City). When criticized over the delay in repairs at Schenley Park, Roessing responded, “We are trying to put something back together overnight that has been rotting away for 40 years.”37

38

38

At long last, Phipps re-opened its doors on Nov. 6, 1938 after being closed to the public for 20 months. Fall Flower Show debuted in pristine, restored glasshouses to enthusiastic praise; reporter Diana Parks of The Pittsburgh Press raved, “The whole place is so beautiful and some of the rooms so restful that I was loath to come away.”38

Phipps surged into the late 1930s in a period of regrowth. The extensive restoration included plants as well as glasshouses: In 1937, the City of Pittsburgh acquired the Clemson Orchid Collection for the Conservatory and by fall 1938 the permanent plant collections numbered about 5,000 species and varieties, one of the largest collections under glass at that time. Their value was approximately one million dollars.

In December 1938, the first Winter Flower Show premiered, featuring poinsettias, cyclamens and begonias. The Pittsburgh Society of Sculptors collaborated with Phipps to display their artwork and supplement educational programs. In 1939, outdoor water features arrived at Phipps with the installation of one water lily pool (now one of two pools forming the Aquatic Gardens adjacent to the Victoria Room) and the dedication of the Steward Johnston Memorial Fountain on April 27. The fountain is found today in the Outdoor Garden and commemorates a lifelong Pittsburgher and avid iris enthusiast; in fact, the three water spouts on the fountain are framed by stone irises.

With new developments at Phipps came a need for more staff. By May 1939, the Conservatory employed horticulturists DeWerth and Curto, as well as six florists, four florist assistants and 13 laborers.

Fall Flower Show, 1939, Cloister Garden

The 1940s and 50s brought more exciting changes to Phipps. On November 6, 1940, four new chrysanthemum varieties that were hybridized at our Conservatory were displayed in Fall Flower Show. These were known as the “Pittsburgh mums” and were revolutionary because at this time, experimentation of this kind in the United States was performed only at universities. Only days later on Nov. 13, Horticulturist Adolphe DeWerth reported a groundbreaking experimental success: The cultivation of a nutrient-rich gelatin which reduced orchid seed germination time from one year down to four to six months. For DeWerth, this meant that Phipps could continue to produce rare hybrids while expediting the time between a young orchid’s germination and first bloom.39

In another instance of “hybridization,” Phipps initiated collaborations with multiple Pittsburgh institutions, joining forces with the Pittsburgh Horticultural Society and the City of Pittsburgh. This partnership proved a boon to the Conservatory’s exhibits; attendance in 1941 exceeded 250,000 guests. Easter Sunday of 1942 set another record for Phipps after 16,000 guests flooded the glasshouses beginning at its 8 a.m. opening and lasting through the day. Guests packed into the Conservatory at so quick a pace that the cacti house was closed off due to becoming a traffic bottleneck.40

Phipps commemorated its 50th anniversary in 1943 with a ceremony held on April 3, just before the opening of the colorful Spring Flower Show. City and Parks executives were invited to an exclusive preview of the show; the wife of Pittsburgh mayor Cornelius D. Scully placed a wreath before a portrait of Henry Phipps painted by famed classical French painter Theobald Chartran in Palm Court. The portrait can still be seen today just outside the auditorium in Botany Hall.41

And with the marking of 50 years of Phipps came a period of exciting developments! In 1946, Assistant Horticulturist Frank Curto was promoted to horticulturist of the Conservatory. Curto, a native Pittsburgher, had graduated from Ohio State University with bachelor’s and Master of Science degrees; Curto had taken time away from the Conservatory during World War II to serve in the Air Force. Now returning four years later, Curto was promoted to lead the Division of Conservatories and Gardens for the Parks Department. During his tenure of nearly 30 years, Frank Curto would make remarkable developments at Phipps, serve as a guest speaker at educational institutions and collaborate with other organizations — including a Spring Flower Show of his design in downtown Pittsburgh’s Kauffmann’s department store.42 In 1948, he was credited with producing brilliant and healthy blooms for the year’s Spring Flower Show by switching from dry fertilizer, which at times burned the plants, to entirely liquid fertilizer for all Conservatory flora.43

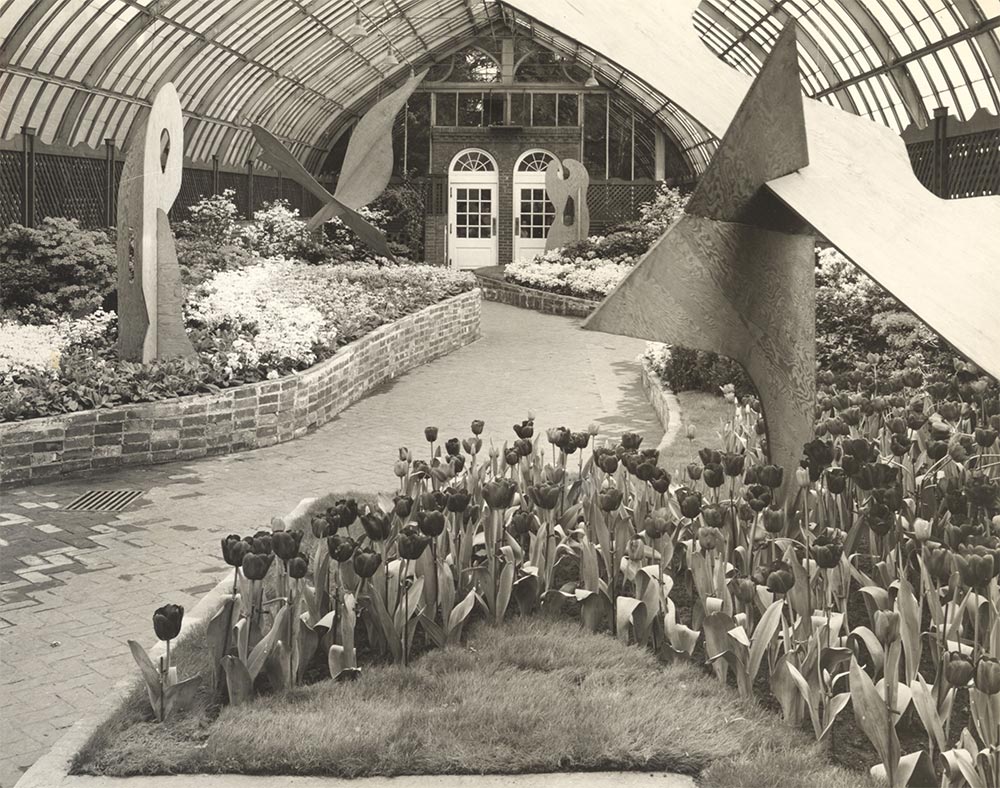

Spring Flower Show, 1948, Serpentine Room

The 1950s saw new plants and renovations refresh Phipps for the latter half of the 20th century. In June 1950, two 14-foot rubber trees were added to the Conservatory as a gift from U.S. Rubber Company.44 Also during this year, four redwood trees were planted at Phipps— as of January 1970, the tallest redwood had reached 25 feet!

The Sunken Garden as we know it today was crafted in 1951 with a renovation of “Exhibition A,” also known as the Baroque Garden. The iconic three brick fountains and the narrow canal connecting them were added in time for Fall Flower Show. The current Fruit and Spice Room was at this time known as the Cabin Room, and in 1951 the room included an old Pennsylvania gristmill and two miniature cottages constructed with wood from a farmhouse originally built in 1833. These structures would be removed in 1991.

The two boiler rooms at Phipps were consolidated into one in 1951, with the original boiler operating with gas or coal. The Victoria Room received a large electric water fountain in 1952; the installation was a gift of the Wherrett Memorial Fund of the Pittsburgh Foundation and purchased from the Briner Electric Company of St. Louis. The fountain added a dramatic effect to flower shows until its removal in 1993.

Also in 1952, the Henry Oliver Rea Estate donated several art pieces to the Conservatory: The Mercury statue and marble fountain base, two lead putti cherub figures and an Italian well of carved stone with a wrought iron structure. All three of these additions are still in Phipps’ collection; the cherubs are on permanent view in the Palm Court while the well now stands as Phipps’ official wishing well in the Broderie Room.

In 1956, Phipps partnered with the National Chrysanthemum Society of America at the 62nd annual Fall Flower Show. The Society displayed a national exhibit of chrysanthemums according to class in what is now known as the Serpentine Room. The chrysanthemums were judged and awarded ribbons and trophies.45 The Serpentine Room’s signature curves disappeared temporarily from 1956 – 1957 when the curving brick walls were removed and rectangular-shaped gardens took their place. The room’s name was changed to the Border Garden.

Phipps has long enjoyed a collaborative relationship with Pittsburgh’s flower arrangement artisans. In 1957, the first display of the Guild of Flower Arrangers occurred at the semi-annual Phipps flower show. In later years, ikebana societies of Pittsburgh would regularly bring the art of Japanese flower arrangement to Phipps. 1959 also saw the installation of the first sound system in the glasshouses, with a more modern and comprehensive system arriving in 1992.

1958 and 1959 saw additional Conservatory collaborations with Pittsburgh artists: The Bonsai Club presented its first exhibit at Phipps alongside Spring Flower Show.46 Bonsai plants are now regular installations in the Gallery Room and Tropical Fruit and Spice Room and are showcased in the annual Orchid and Tropical Bonsai Show. In the following year, Phipps celebrated Pittsburgh’s bicentennial anniversary with the display of a bicentennial seal formed entirely out of chrysanthemums and a two-day exhibition from the Western Pennsylvania Orchid Society.47

The Conservatory’s plant collection grew again in the early 1960s. Cymbidium orchids were donated in 1960 by Dos Pueblos Orchid Company owner Samuel B. Mosher, and the 100 blooms valued at $5,000 went on first display for Spring Flower Show. In 1962, Miami Beach shipped eight full-sized coconut palm trees to Pittsburgh to commemorate the Sept. 15 Pitt vs. Miami football game. These trees were displayed at the northern end of the stadium before finding a home in the center area of Palm Court just in time for Fall Flower Show’s opening day. The coconut palms replaced two palm trees that had thrived at Phipps since its 1893 opening but were now tall enough to push through some of Palm Court’s glass panes, as illustrated below in The Pittsburgh Press.48

When the 1962 Fall Flower Show opened on November 11, the Conservatory was open with free admission from 9 a.m. – 5 p.m.; from 7 p.m. – 9 p.m., admission was 50 cents for adults and 10 cents for children. This was an increase from the 1935 evening admission costs, but was met with support from Pittsburghers because of our Conservatory’s strong reputation as one of the best botanical gardens in the world.49

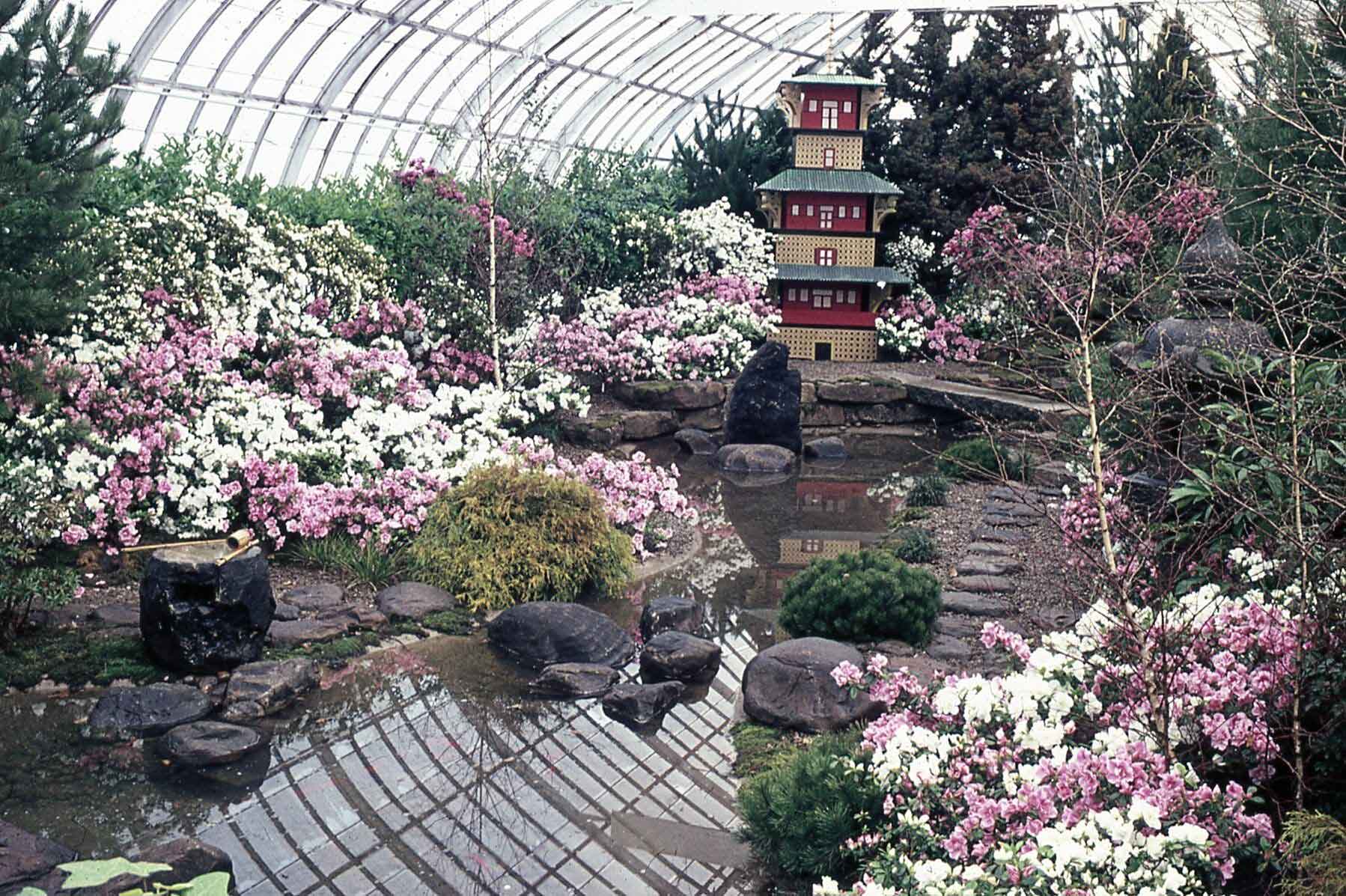

In 1963, the Cascade Garden (in what is now known as the East Room) was demolished. Frank Curto drew inspiration from his 1962 research trip to Japan and installed a display reminiscent of the gardens of the country, featuring a tori gate, arranged native stones and water features. The Japanese-style garden was ready in time for the 1963 Spring Flower Show, and was described as “timeless.” 50 A small wooden pagoda and large ornate lantern decorated the garden until the spring of 1964, when a bamboo teahouse took its place.

Horticulturist Frank Curto, now 56 years of age and pictured in his Japanese garden above, celebrated 30 years at Phipps on Nov. 15, 1964. Curto was by now Pittsburgh’s premier expert in ornamental horticulture, having served as secretary-treasurer for the Pennsylvania Nurserymen’s Association and as a charter member of the Men’s Garden Club of Allegheny County; he also hosted a 30-minute Saturday morning television show on gardening. His passion for his work was exemplified in the new Japanese-style garden, which Curto explained according to his recent visit to Japan: “They have a feeling toward the intimate and useful. Their gardens are more than the mass displays to which we are accustomed.”51 His greatest satisfaction upon completing work such as this inspired garden was “seeing people ranging from small children to elderly persons coming to the flower shows and enjoying them.”51

Another garden space in the Conservatory underwent renovations in 1964. The Cloister Garden was dismantled after 29 years, and landscape architect Ralph Griswold was commissioned to design what we know today as the Broderie Room. The “Broderie” style of Garden followed the 17th century “Parterre de Broderie,” or “embroidery on the earth” garden pattern. To aid appreciation of this design the garden was depressed and then inclined towards the rear of the space. A lattice trellis constructed of California redwood circled the perimeter, and ornamental Oxford bricks topped the wall at the entrance to the garden and formed the edges to the steps. This brick was sourced from Alwine Company in Gettysburg, PA. Broderie Garden construction involved a group effort with Phipps staff, City of Pittsburgh Department of Lands and Building and the Division of Construction and Repairs of the Parks Department. Design and materials were funded by longtime Phipps affiliates, the Garden Club of Allegheny County.

Phipps' stunning orchid collection grew again in June of 1965 when Allen Kerr, United States Embassy to Thailand, donated 1,200 Thai orchid species.

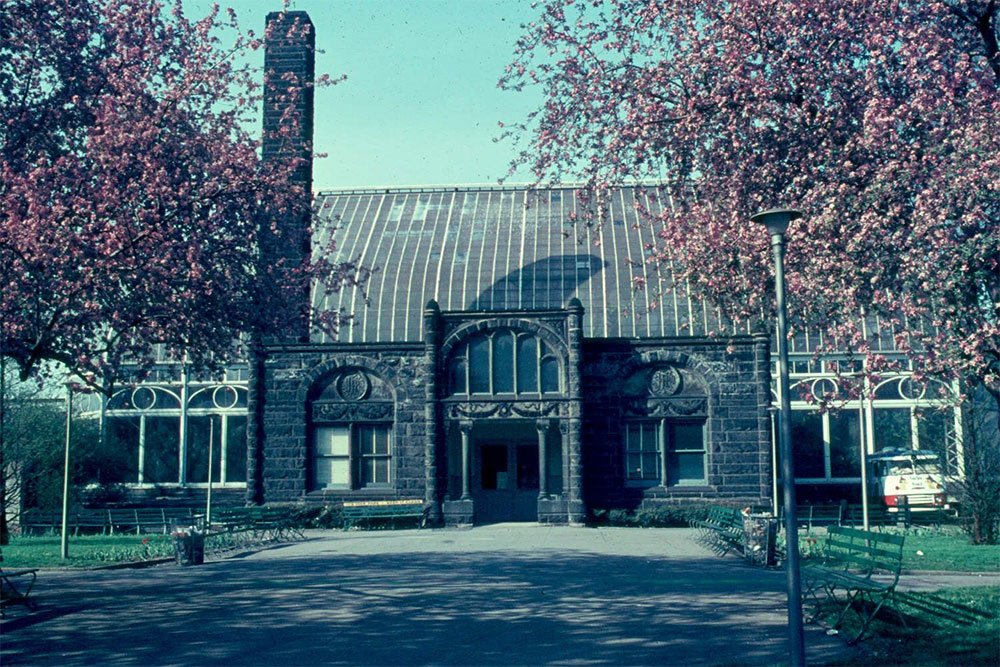

In April 1967, the original Richardsonian Romanesque entrance to Phipps was demolished. A new structure was completed for the Spring Flower Show debut in 1968 and contained offices, a meeting area, restrooms and a full basement for storage. It cost $183,500, was designed by Pittsburgh architect John Whitley Cavitt and was constructed by the Joseph Massaro Construction Company. The stone used on the sides and front of this new entrance was the Amherst sandstone from the original building; stone walls in the lobby were also sourced from the original structure. At this time the 1892 date medallion was moved from the west side of the original entrance to its current position in Palm Court above the arched doorways into the South Conservatory. This impressive medallion required 11 hours of meticulous installation work by a stonemason and assistant!

Phipps received another generous art donation in June 1967: Three bronze sculptures by Edmund Armateis were given to the Conservatory by Richard Scaife from the Mellon Estate in Rolling Rock, PA. These sculptures originated from the garden of the Mellon house in what is now Mellon Park, the location of the Phipps Garden Center. The sculptures are viewable in the rear of the Broderie Room.

New aesthetics developed at our Conservatory at the end of the 1960s: In 1968, pipe and cork “pretend” trees were installed in the Orchid Room; today they still reach over the fish ponds at the center of the room. Bromeliads were attached to the branches.

The 1969 Fall Flower Show celebrated the Diamond Anniversary of Phipps. The South Conservatory (then known as the Economic Room) featured a large floral diamond covered in white chrysanthemums.

The 1970s brought changes to Phipps' art collections, operations, affiliates and more. On Oct. 12, 1970, James N. Spear of New York presented a small collection of artworks from his Pittsburgh estate to the Conservatory: Five large terra cotta vases, a miniature limestone pagoda, a matched pair of stone lanterns and a third stone lantern. Four of the terra cotta jars remain in Palm Court; all other artifacts are currently located in today’s Japanese Courtyard Garden.

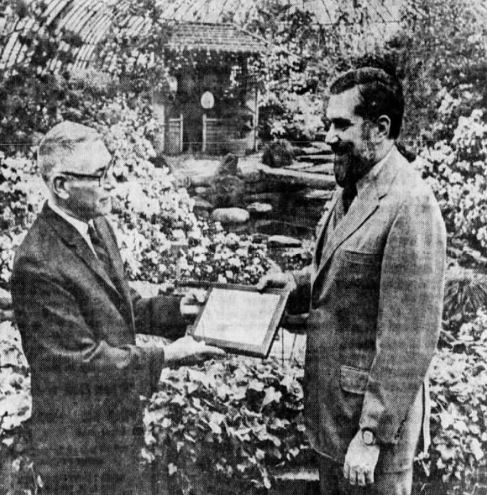

On Nov. 25, 1970, Frank Curto resigned as director and horticulturist of Phipps at age 62 due to poor health. “Mr. Flower Man of Pittsburgh” ended a 34-year career at Phipps after having served 25 of those years at the helm.51 Curto had been presented with the Sylvia Award in April from the Society of American Florists, receiving the highest honor from the world’s largest florist organization. The plaque on the award read: “In recognition of untiring labors and distinct achievement in outstanding benefit and interest to his community and fellow men.”51

51

51

Curto formally received the Sylvia Award while standing in his prized Japanese-style garden in today’s East Room. This accolade and many, many others decorated Curto’s highly influential career, and many Pittsburgh professional and amateur gardeners sought his expertise year-round. And so it was a loss to Phipps Conservatory when Frank Curto retired in November 1970, and a loss to the worldwide horticultural society when Curto passed away on Feb. 23, 1971.52

Citations

31. “Noteworthy Orchid Group Given to City.” The Pittsburgh Press (1932): 17. Newspapers.com.

32. “No. 261.” The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette 6 no. 52 (1932): 16. Newspapers.com.

33. “Mrs. James D. Hailman Helping Rehabilitation of Phipps Conservatory.” The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette 5 no. 151 (1935): 12. Newspapers.com.

34. “Gale Causes Big Damage at Phipps Conservatory.” The Evening Standard 49 no. 56 (1937): 1. Newspapers.com.

35. “WPA Will Repair Phipps Conservatory.” The Pittsburgh Press (1937): 39. Newspapers.com.

36. “This Fall’s ‘Mum’ Show to Be Held at West Park.” The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette 11 no. 51 (1938): 17. Newspapers.com.

37. “Conservatory is Scene of Annual Show.” The Pittsburgh Press (1938): 43. Newspapers.com.

38. “Months Cut Off Time Needed to Raise Orchid From Seed.” The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette 14 no. 91 (1940): 24. Newspapers.com.

39. Sunny Easter Day Overfills Churches with Worshippers.” The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette 15 no. 213 (1942): 13. Newspapers.com.

40. “Phipps Conservatory Marks its 50th Year.” The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette 16 no. 211 (1943): 2. Newspapers.com.

41. “Kauffmann’s Eleventh Floor Auditorium Flower Show.” The Pittsburgh Press 68 no. 322 (1952): 18. Newspapers.com.

42. “Liquid Fertilizer ‘Secret’ of Flower Show Brilliance.” The Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph 42 no. 49 (1948): 54. Newspapers.com.

43. “Phipps Conservatory Receives Gift of Two 14-Foot Rubber Trees.” The Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph 46 no. 119 (1950): 34. Newspapers.com.

44. “National Mum Show Here Next Week.” The Pittsburgh Press 73 no. 127 (1956): 55. Newspapers.com.

45. “Bonsai Club Shows Dwarf Trees Here.” The Pittsburgh Press 74 no. 292 (1958): 108. Newspapers.com.

46. “Fall Flower Show Will Open at Phipps Nov. 8.” The Evening Standard 70 no. 264 (1959): 9. Newspapers.com.

47. “Gilbert Love’s Notebook.” The Pittsburgh Press 79 no. 105 (1962): 25. Newspapers.com.

48. “Just as Sweet.” The Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph (1960): 19. Newspapers.com.

49. “Better Than Before: That’s Flower Show.” The Evening Standard 74 no. 104 (1963): 1. Newspapers.com.

50.“Curto Says ‘First Love’ is the Japanese Garden.” The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette 38 no. 101 (1964): 80. Newspapers.com.

51. “Awards Faint Echos to Curto’s Gifts to Gardening.” The Pittsburgh Press 86 no. 275 (1970): 101. Newspapers.com.

52. “Pittsburgh’s Flower Man Dead at 62.” The Indiana Gazette 71 no. 200 (1971): 11. Newspapers.com.