Blog

#bioPGH Blog: Tulipmania!

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

Nothing quite says spring like a garden full of colorful tulips! Originally from Asia, these beautiful bulb flowers and their close relatives have been a springtime delight in the Western world for at least four hundred years after trading popularized them in Europe. Today, naturalized “wild” tulips can be found in parts of Europe and in North America, but we in the US still classically associate them with horticulture, particularly around the same time of year when the surprise snow flurries have finally stopped and the sun comes out. We may have a few weeks before our tulips outside are in full bloom, so while we wait impatiently, let’s explore a bit of the history and biology of these hallmarks of spring, shall we?

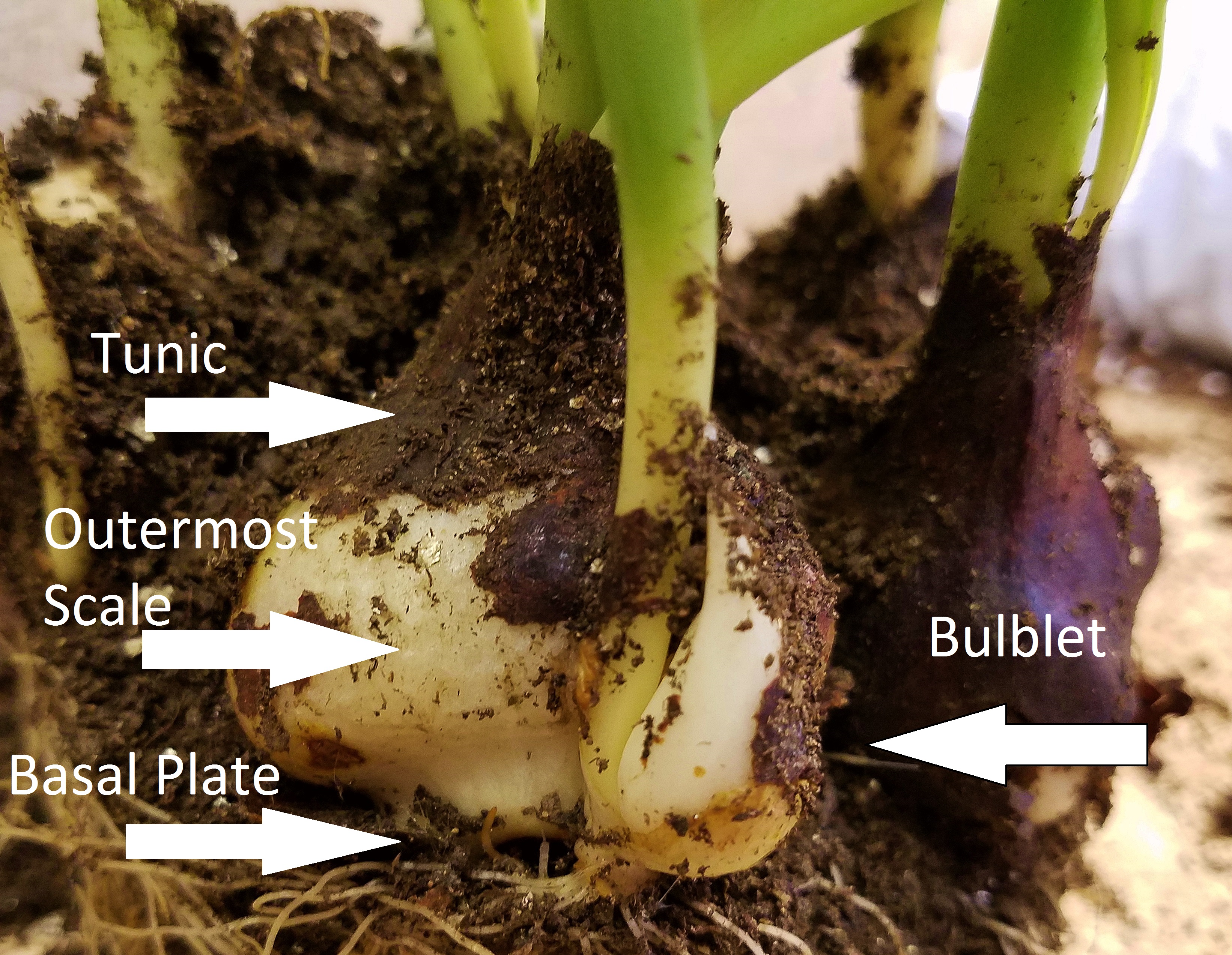

Tulips are members of the lily family (Liliaceae), and the horticultural varieties many of us are familiar with can have smooth petals or petals with wavy edges, and their color can be solid or variegated—meaning they can have different color petals. As a defining botanical feature, tulips are “bulbous” flowers, with the ability to grow from bulbs. A bulb is an interesting structure—more complicated than meets the eye! The bottom of a bulb will have what is called the basal plate. The roots of the bulb will extend out from the basal plate, and the thick, fleshy nutrient storage scales (the bulk of the bulb body) extend upwards from the plate. Coating the outside of the fleshy scales is a protective tunic, and each year’s new shoot will begin in the center of the bulb. After their spring bloom, the plants go dormant and need a cool period before they can bloom again. Eventually, new little bulblets form alongside established bulbs.

As much as we love tulips in the spring, it’s nothing compared to the tulip frenzy in seventeenth century Holland. Legends and lore abound of the bulbs that were used instead of currency, and the mad search for multi-colored tulips. When we consider the actual historical evidence of “tulipmania,” though, it is more likely that the dramatized depictions of the intense popularity rise and fall were more likely the inflated version of reality—exaggerations meant as a cautionary tale of economic bubbles, rather than an actual historic account of tulips wrecking the Dutch economy. There was never a sailor jailed for eating a tulip bulb he had mistaken for an onion, and there doesn’t seem to be any evidence for the story of an entire estate traded for a bulb that promised a multi-color flower. Still, though, we know that tulips were highly prized in the seventeenth century. The flowers that bloomed in extravagance for only 1-2 weeks were quite a status symbol, and they did indeed occupy the interests of merchants, particularly those involved with the Dutch East India Company. Though the original story of tulip fever may have been an exaggeration, the Netherlands remain the world’s largest producer of tulips and have exported over two billion tulips per year in recent years.

While you wait for our outdoor tulips to bloom, you can check out tulips by the hundreds in Phipps’ spring show Scents of Wonder. The bulbs are changed as blooming finishes, but over the course of the show, roughly 36,000 tulips will be on display! And let’s not forget the other bulb flowers—the thousands and hyacinths, daffodils, amaryllis, and all of the other colorful beauties.

Connecting to the Outdoors Tip: If you weren’t able to prep bulbs for the spring, never fear! With a little work, you can “force” a bulb to bloom out of season, and may even get to observe root development as it happens. Check out these instructions from the Virginia Cooperative Extension of Virginia Tech and Virginia State University, and see how you do!

Smithsonian Magainze: There Never Was a Real Tulip Fever

University of Illinois Extension: Bulb Basics

Encyclopedia Britannica: Bulbs

Photos by Paul g. Wiegman