Blog

#bioPGH Blog: The Full Circle of Nature’s Autumn Spectacular

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

It’s starting! A bit of yellow here, a blush of red there, a peek of orange off in the distance — our leaves are starting to change color! As the next few weeks progress, we will be treated to the brilliant annual display of color that marks autumn in a temperate deciduous forest. Besides showing off dramatic colors, though, leaf fall is a crucial winter survival tactic for our trees. Let’s explore this through the full life story of a leaf!

Imagine your favorite tree on a day in late winter or early, early spring, before we can see even the slightest hint of green. If we zoom in on that tree to a single vegetative bud — a bud that will produce a leaf — we can follow the life of that leaf. Just after budburst, this leaf will appear green yet often slightly tinged red. This red comes from a build-up of plant pigments called anthocyanins, once thought to act as a natural sunblock for the young leaf, but possibly to serve as a deterrent for hungry herbivores. Many leaves, though they will be green when mature, start off with other pigments visible.

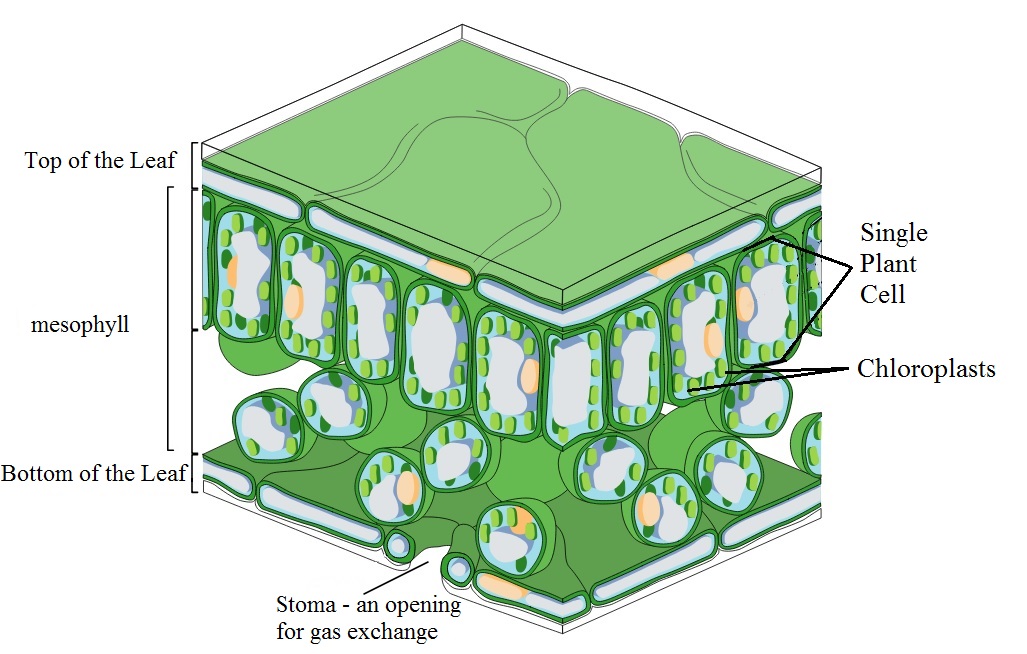

Our leaf friend will mature in spring; and throughout the spring and summer, tree leaves have an essential job to do: photosynthesis. In this process, the energy from the sun powers the chemical reaction in a leaf that converts carbon dioxide and water into oxygen and sugars. If you look at the diagram of a zoomed-in leaf below, photosynthesis is occurring in the chloroplasts (a type of organelle, or “little organ”) of plant cells. Each cell has many chloroplasts, and these chloroplasts are full of the pigment chlorophyll, which facilitates photosynthesis. The chlorophyll is also what gives leaves their vibrant green color.

As summer leads to autumn, our leaf will change colors with the other leaves on their tree and contribute to our view of vivid reds, yellows, oranges, and even purples. Temperature and the change in photoperiod (day length) signal for plants to cease photosynthesis for the season. Existing chlorophyll breaks down, and the colors that emerge are from other pigments in the leaf such as the anthocyanins we mentioned earlier, which display red and purple, and carotenoids, which reflect yellow, red and orange light. Those pigments were also present during summer, but they were masked by the more abundant chlorophyll.

Now here is the key question: why is it so important that those leaves fall? In a nutshell, it’s because leaves have no purpose in the winter. We mentioned that the most important job of a leaf is photosynthesis, but when the weather is too cold, enzymes (molecular “machines”) in leaves can’t properly function, and thus can’t photosynthesize. On top of that, ice formation can destroy leaf tissue, which is energetically expensive for a tree to repair. Overall, that means during the winter, leaves would simply be a costly but non-functional feature — so it’s much easier and more efficient to just let them go every fall and regrow in the spring.

After their dramatic change in color, our leaf and those on neighboring branches will eventually fall from the tree — but their story is far from over. Now starts the next phase of life for the leaf as a part of leaf litter on the forest floor. Don’t worry about the word “litter,” though; leaf litter is critical part of forest ecology — especially in our temperate part of the world. The leaf litter helps the ground maintain moisture, it provides a home for a wide variety of creatures, and it acts as a food source for insects and other tiny organisms which start breaking down the full leaves. Smaller bits of leaf material are further decomposed by fungi and bacteria, which helps break down the leaf into new soil and nutrients—the final stage of a leaf’s story. This whole process of leaf decomposition depends on number of factors, like temperature, shade, moisture, soil chemistry, and even the type of leaf; but the end product feeds new life on the forest floor. A variety life depends on this replenishing of nutrients, including microbes and plants, which in turn support insects, larger animals, and beyond. And next year, the trees will form new leaves and begin the process all over again.

Hopefully you will have a chance to go for a hike sometime soon and enjoy the beauty and magic of nature’s yearly processes. And even when the colors are gone, we can appreciate the brown leaves even more!

Connecting to the Outdoors Tip: If you have time to wander through the leaves, allow your mind to be empty. Give yourself permission to forget the rest of the world for even just an hour. Turn off your electronics, if you can. Don’t walk for speed or calories burned — just meander. Don’t make yourself feel anything or be anything. I will fully admit that this is actually quite difficult for me; I have to be intentional. But my goodness do we all need some time for refreshment!

Continuing the Conversation: Share your nature discoveries with our community by posting to Twitter and Instagram with hashtag #bioPGH, and R.S.V.P. to attend our next Biophilia: Pittsburgh meeting.

Resources

MIT News: The mathematics of leaf decay

SUNY ESF: Why Leaves Change Color

Images: Cover, Pxhere CC0; Header, Wikimedia User dcrjsr, CC-BY-3.0; Leaf structure, adapted from Wikimedia User Zephyris CC-SA-3.0; Decomposition, Wikimedia User Cedrick May CC-BY-SA-4.0; New leaf, Wikimedia user Evelyn Simak, CC-BY-SA-3.0; colorful leaves OregonDOT