Blog

#bioPGH Blog: Prolific Pollen!

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

Your eyes are itchy and watering as you reach for the tissue box. The sinus pressure! The sneezing! Oh, those seasonal allergies! If that scenario sounds familiar, you’re not alone in your sniffly suffering. According to the Allergy and Asthma Foundation of America, over 50 million Americans experience allergies and the CDC reports at least 19 million adults diagnosed with hay fever. And this time of year, we eye up a yellowish, powdery culprit for the allergy affair: pollen. Pollen is a crucial part of plant reproduction, meaning we obviously need it around; but were we always exposed to this much pollen in the spring? Or is something else possibly at work here? Let’s explore!

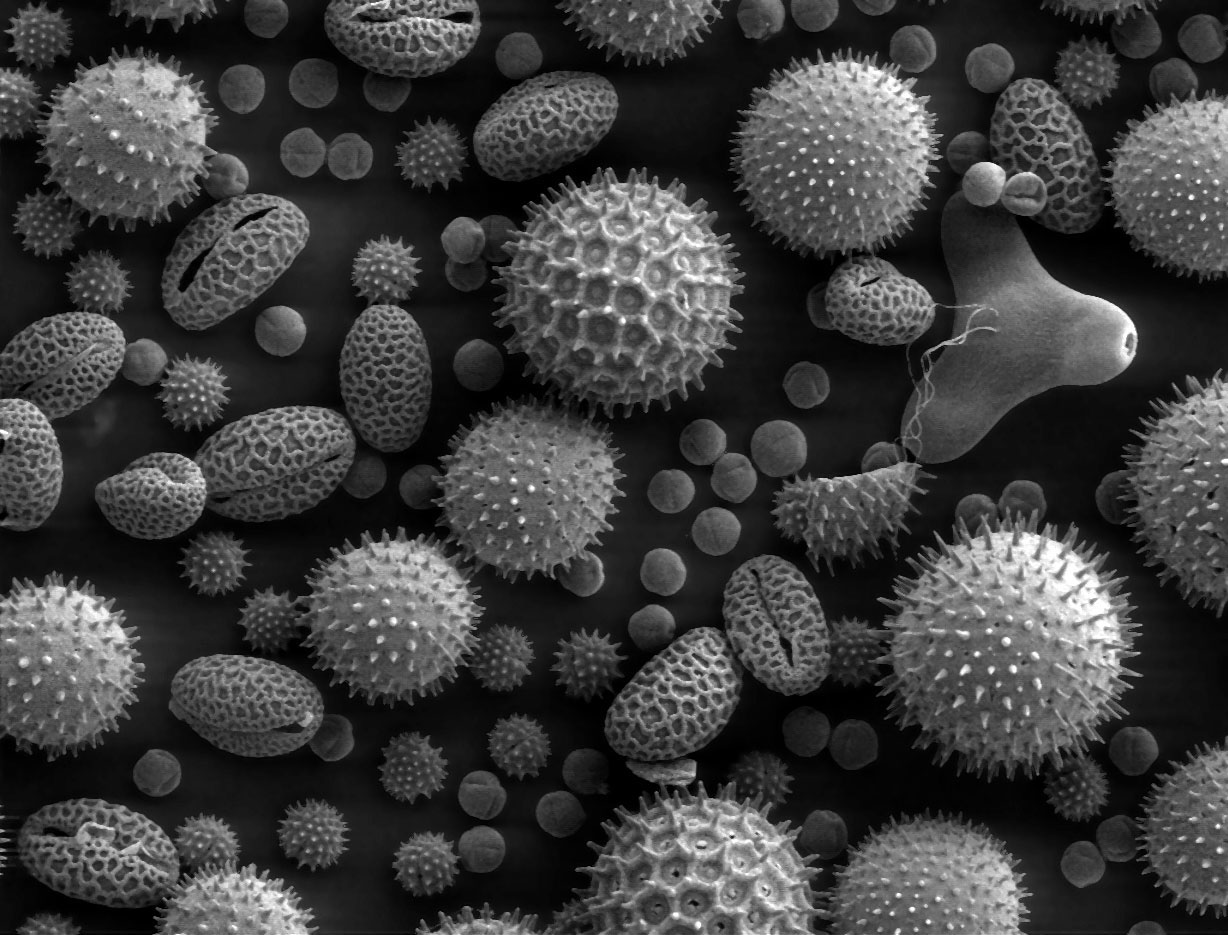

First, what is pollen? Pollen grains are essentially little delivery packages for the plant version of sperm (male gametes). They are produced on the anthers of flowers or by the male cones of conifers and other non-flowering plants and trees. Following production, they are carried away either by a pollinator such as bees, butterflies, bats, etc., or to our allergies’ dismay, by the wind. Pollen is microscopically tiny, and when carried about in the air, it’s quite easy for us to accidentally breathe it in or rub it in our eyes.

Variety of pollen grains, Photo: NASA/Goddard Flight Center

For those of us who suffer from seasonal allergies, pollen triggers an immune response; but seasonal allergies like we experience today weren’t common 50-60 years ago and earlier. But why is that? Well, allergies overall have been on the rise over the past several decades, but hay fever itself seems to have a complicated interweaving of factors behind it. Notably, city planners have traditionally planted male trees when possible to avoid the “litter” left behind by the fruits of female trees. This technically should only have been possible for dioecious trees (trees with male and female flowers on separate individuals), but through careful pruning and grafting, arborists were also able to produce male-only plants of species that normally are monoecious (male and female flowers on the same individual). Since pollen comes from males, the excess of male trees produces quite a bit of pollen in our cityscapes. In addition, since cities tend not to plant a diversity of species, it’s often an excess of males of the same species producing a plethora of pollen. The pollen of non-native species can also be problematic for allergy-sufferers, and the push for native plants is relatively recent when we look back on a century of city planning. Another huge factor is the compounding effect of pollution.

Pine pollen, image: National Park Service

Temperature can also play a role in pollen production. We know that cityscapes tend to be warmer than suburbs and rural settings due to the urban heat island effect, and some studies have shown that plants growing in these warmer, urban environments can produce more pollen than their non-urban counterparts. This would give city residents more pollen to contend with. Then, of course, we all have to contend with the higher pollen counts due to climate change, which both can increase pollen production in plants and increase the length of pollen season.

So, pollen is indeed on the rise and allergies are on the rise, but there certainly things we can do. Opting for a variety of native tree species, planting male and female trees, and advocating for cleaner air can all help us breathe a little easier. In the meantime, pass the tissues!

Note: In conversations about “botanical sexism,” (the planting of predominantly male trees in cities) a 1949 USDA document is frequently but inaccurately invoked as offering the following advice: “When used for street plantings, only male trees should be selected, to avoid the nuisance from the seed.” This quote lacks context and is actually missing a word. The actual 1949 USDA Yearbook of Agriculture states: “When used for street plantings, only male trees should be selected, to avoid the nuisance from the cottony seed.” This quote was a specific point in a list of reasons why the USDA was advocating against cottonwoods as city trees (the rest of the information included how the wood was soft and susceptible to high winds and the roots had a tendency to grow into pipes.) The same publication actually suggests for “only females” of other tree species to be planted. The book essentially looks at several individual species and their possible uses across different parts of the US, and for dioecious species, they suggest planting whichever sex smells better and sheds fewer flying bits of plant material (more often males, but sometimes females.) However, the word “cottony” is usually dropped when the quote is shared and the context of the statement is not included, which frames the quote inaccurately as the USDA blanket-suggesting only planting male trees when that was not actually the case. You can read it for yourself on page 66 here. However, it is certainly true that around this time, cities across the country began planting predominantly male trees.

Connecting to the Outdoors Tip: If your allergies are particularly brutal, but you love the outdoors, check out the daily pollen forecast to plan out which days may be better for outdoor adventures during the high-pollen times of the year!

Continue the Conversation: Share your nature discoveries with our community by posting to Twitter and Instagram with hashtag #bioPGH, and R.S.V.P. to attend our next Biophilia: Pittsburgh meeting.

Photo Credits: Cover, Wikimedia User Asja Rada CC-BY-4.0; header, Pixabay.