Blog

#bioPGH Blog: Lichen

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bi oPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bi oPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

This post includes guest co-author Cody Jones, one of Phipps’ 2019 Summer Intern Leaders. Cody is a high school senior, and he was a Phipps Summer Intern in 2018. Look for his blog posts this summer as he and the other interns keep us updated on their work at Phipps!

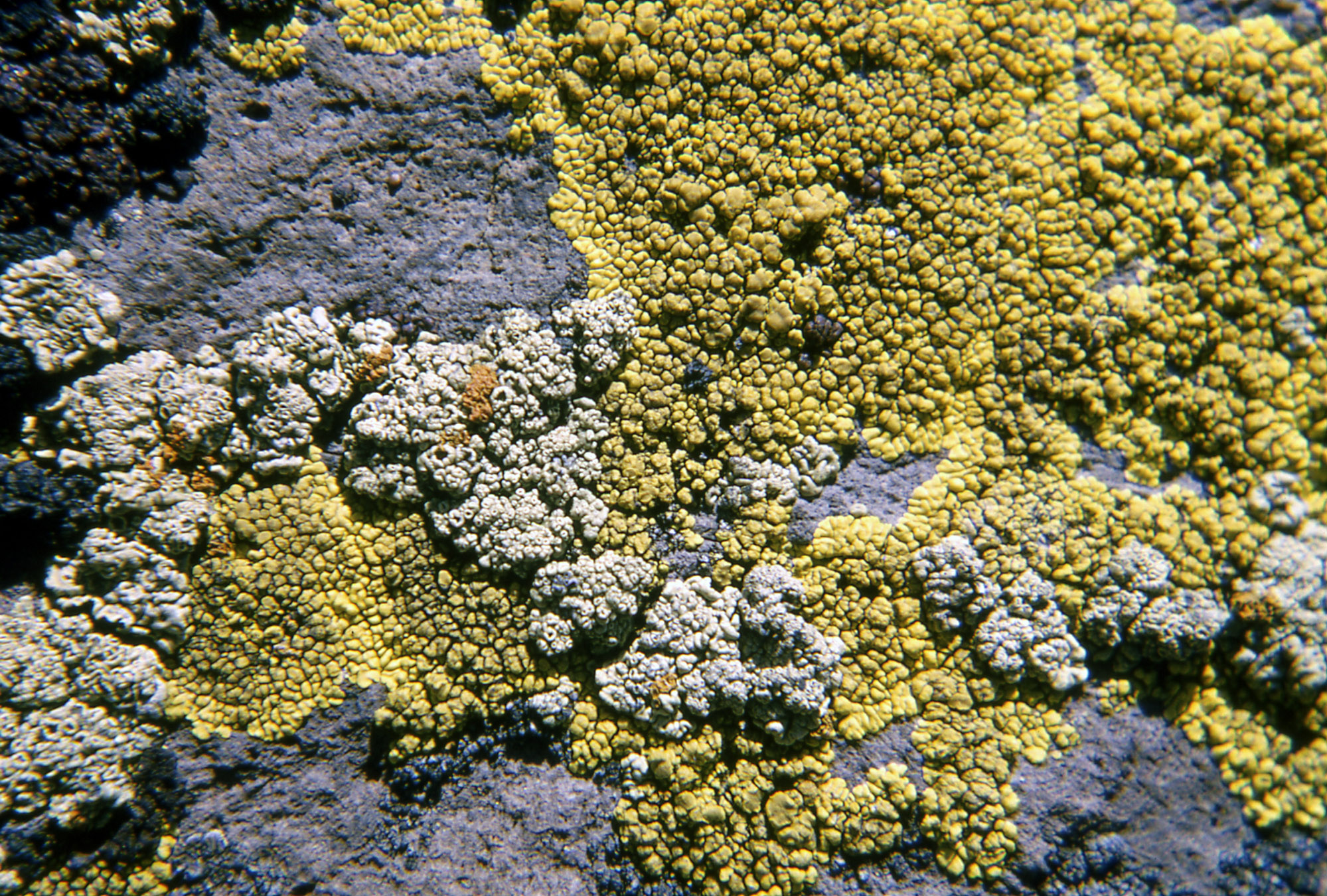

Have you ever seen spots on a tree that may be gray, green, blue, red, yellow, neon yellow (what?), and wondered what all of those little spots or big circles might be? Are they mold? Maybe bacteria? Close! It’s a lichen—so it’s both, and they have to co-exist. Let’s explore!

What is a Lichen?

A lichen isn’t actually a single organism; it’s a combined existence between a fungus and either algae or cyanobacteria. The combined existence works out well as each partner is providing something that the other needs. Normally, cyanobacteria and algae are found in aquatic habitats (both freshwater and marine), but when a part of a lichen, the fungi provides a safe living space. In return, the photosynthetic algae and cyanobacteria provide energy for the fungi. That’s why lichens can thrive on surfaces like rocks and rooftops where it doesn’t seem like any nutritional sources are readily available—their food is being produced in-house.

There is quite a bit of diversity across lichens since different combinations of fungi and cyanobacteria can produce different kinds of lichen. There are roughly 13,000-17,000 different species of lichen in the world, and they can survive in climates ranging from temperate zones to the tropics to the arctic and Antarctic. Broadly speaking, lichen can take on four different shapes, and I’m sure you’ve seen examples of most of them.

Fruticose—These look like little plants themselves! Fruticose lichens can branch away from the surfaces they are growing on, and they can look hairy, leafy, shrubby, or even like little trumpets.

Photo: NPS, Fruticose lichen in gray

Crustose—Lichens this shape appear “crusty” or bumpy and can grow on rocks and other non-living surfaces like your roof or porch.

Photo: NPS

Foliose—If “foliose” reminds you of “foliage,” it will be easy to remember that these lichens are leaf-like in appearance!

Photo:Bernd Haywold

Squamulose—These lichens are somewhat scaly—not quite crusty like crustose, but not quite as leafy as foliose. You may not always find squamulose noted as a shape in books or other natural history resources since it has been referred to as an intermediate shape.

Photo: Eric Guinther

Lichens as Indicators of Air Pollution

Intriguingly, lichens are especially useful as bioindicators, which means we can learn about the quality of their habitat through their presence, absence, or the different kinds of lichens present. Lichens, unlike most vascular plants, absorb nutrients from their entire surface area as opposed to plants absorbing nutrients just through their roots. When air pollutants are absorbed onto the lichen’s surface, the algae can be killed or damaged, and the lichen can become discolored or reduced in size. Over time, lichens that are more sensitive to air pollution can start disappearing from a habitat and be replaced by more pollution tolerant lichens.

Though there are a few different factors to consider, but in general, crustose lichens tend to be the most resistant to air pollution. These are the lichens that lay flat against a surface, and it seems pollutants are less likely to accumulate and damage these kinds of lichen—possibly because less surface area is exposed to the air. Foliose species are generally resistant to pollution, but not as much as the crustose. At the end of the list, fruticose, with its three-dimensional shape, is the most vulnerable to pollutants. By scouting out the lichens in your area, you can get a general idea of local air quality, and if more crustose are present than any other type, it might be time to investigate!

Connecting to the Outdoors Tip: The National Park Service suggests documenting lichens on iNaturalist the next time you’re out exploring in the woods or in your area. This will help experts compare air quality to lichen population data!

Resources

Utah State University, Intermountain Herbarium—Lichens

Park et al. 2014—Algal and Fungal Diversity in Antarctic Lichens

Porada et al. 2014—Estimating impacts of lichens and bryophytes on global biogeochemical cycles

Giordani et al. 2011: Functional traits of epiphytic lichens as potential indicators of environmental conditions in forest ecosystems

Photo credits: Squamulose lichen, Eric Guinther, CC-BY-SA-3.0; Crustose, National Park Service, public domain; Foliose, Bernd Haynold, CC-BY-SA-3.0; Cover image, Maria Wheeler-Dubas