Blog

#bioPGH Blog: Big Brown Bats

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

The night sky was dark and clear, dotted with little flecks of light from the stars. Around the shrubs and tree, fireflies glowed here and then there and over there. And in the still, you could faintly hear the high pitch chattering of furry-winged nighttime neighbors — bats! Even in the dark, the outline of a bobbing flier was clearly visible and distinctive from the silhouette of a bird in flight, and as I waved a mosquito away from my ear, I gave that little insectivore in the sky a head nod. Enjoy your dinner, little friend, I thought I appreciatively. What kind of bat was it I saw from my backyard? Admittedly, I didn’t get a close look, but it most likely was the big brown bat (Eptesicus fucus). The big brown bat can be found across North America and into Central and South America, and it is the most common bat in Pennsylvania. Bats like this one and others can sometimes cause a bit of anxiety, particularly if you see one close by; but there’s no need to be afraid of these little winged neighbors — they’re fascinating! Let’s explore!

The big brown bat may be big compared to some other species of bat, but they still are quite small as creatures go. They may be up to 5 inches across in wingspan, and weigh at most as much as three US quarters (0.55 ounces). As small as they are, big brown bats can do quite a number on pest insect populations — females with young can even eat their body weight in bugs on a nightly basis! Some of their preferred diet items include beetles, some species of which can wreak agricultural havoc.

One fascinating angle of bat biology is their ability to use echolocation, or bouncing sound off their surrounding environment to “see” their world. Big brown bats use this ability to detect insects flying as much as 16 ft away. This is impressive on its own, but what is truly astounding is that bats must be able to balance out acoustic information they are receiving about larger and more distant features in their environment (e.g. trees, buildings, etc.) while also gathering formation about the smaller, quickly moving diet items are searching for — after all, there is a lag time while sound is bouncing back from faraway structures, but bats need to call again as quickly as possible to hear objects in rapid motion, like flying insects. To manage this, big brown bats will alter the intervals between their calls, depending on how “cluttered” the environment is, to ensure they are receiving up-to-date information about the dark nighttime world around them.

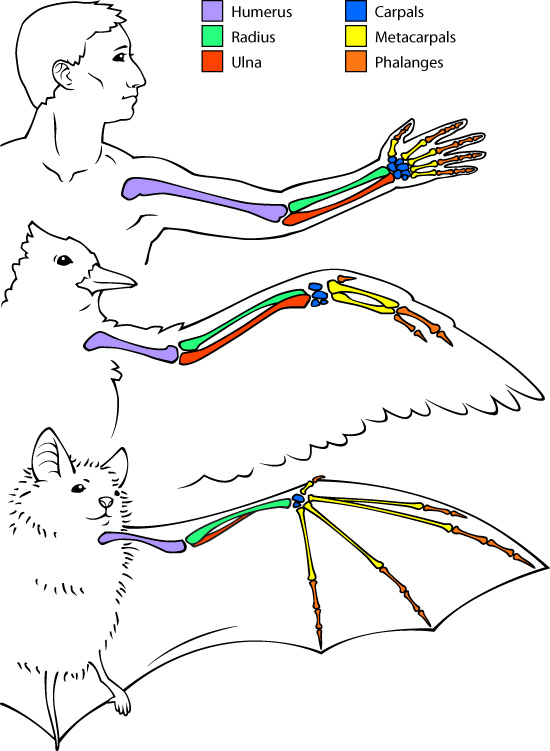

Besides echolocation, bats are also known for their aerial abilities. In fact, though some animals like flying squirrels and lemurs can “glide” through the air, bats are the only mammals capable of true flight. They accomplish this in a slightly different way than another large group of fliers, the birds. If you look at the skeletons of birds versus bats, you’ll notice both some overlap and some differences. For example, you can see in the image below that birds and bats share structures similar to humans and indeed many other animals. The three of us share similar arms bones in the humerus, radius and ulna, but some differences arise after that. For us humans, an assortment of small bones make up our hands and fingers: the carpals, metacarpals and phalanges. In a bird wing, many of those small bones are fused together, or they are short and comparatively stocky. In bats, though, their “hands and fingers” are rather extensive, with their “fingers” making up nearly half of a bat wing (although this varies by species).

Image © Arizona Board of Regents / ASU Ask A Biologist, CC BY-SA 3.0

When it comes to diseases, big brown bats have a slight advantage over some of their bat cousins. Though they unfortunately do have to contend with rabies, not all big browns seem to contract the virus when exposed. In addition, big brown bats do not seem to have struggled with the fungal disease white nose syndrome that has decimated other bat populations. (However, we should all still exhibit caution both to protect ourselves and bats, and keep in mind that the best way to appreciate animals is from a distance.)

So all in all, the next time you see a bat, no need to fear! They are helping us out, and they make excellent wild neighbors.

Connecting to the Outdoors Tip: Big brown bats can sleep in trees, under the eaves of houses, or around barns and old chimneys. If you're outside at night, trying being still and listening for quiet chattering, and watch for something flying that seems to bobble rather than glide. You might just spot yourself a big brown bat!

Resources

PA Game Commission – Big Brown Bat

Image credits: Header, Pexels; Cover, USFWS